How much data do you need to train a seq2seq model? Let’s say that you want to translate sentences from one language to another. You probably need a bigger dataset to translate longer sentences than if you wanted to translate shorter ones. How does the need for data grow as the sentence length increases?

Quick Recap on Seq2seq

Seq2seq is a neural framework for machine learning tasks that involve mapping sequences of tokens to sequences of tokens, such as machine translation, text summarization, or time series prediction. There are two recurrent neural networks, called the encoder and the decoder. The encoder takes a temporal sequence of tokens as input and we don’t really care what it outputs, but we save its internal state vector, which you can think of as a learned representation of the input sequence (a seq2vec, if you will). In the decoding phase, we initialize the internal state of the decoder to that internal state vector that we received from the encoder, and have it try to predict the next token in the sequence given the previous token. During training, we do not pass the output of the decoder from the previous step as input, but rather the actual “correct” token for that timestep from that training example (as we expect the decoder to predict nonsense early in the training process).

There is a tutorial here for using seq2seq to do English to French translation using Keras. The dataset for training comes from Tatoeba, an online collaborative translation project. Tatoeba publishes a dataset of basically (sent1, sent2, lang1, lang2) tuples sourced from its members, where sent2 is a translation of sent1 and sent_i respectively belongs to lang_i. This dataset contains many languages pairs, not just English/French. The dataset in the tutorial has been pre-processed for ease of consumption, and contains about 150k examples ranging from one word sentences to somewhat complicated sentences of 30–40 words.

Translation Performance

If you wanted to train a translation model and actually use it, you would probably want each token to be a word. I tried this and didn’t get anything useful — probably the dataset is too small to be used this way. The tutorial takes each token to be a character (presumably for the same reason), and all the models in this experiments are also trained on a character by character basis. What is amazing is that you can get any kind of coherent translation at all from doing this.

The tutorial model is trained on only the first 10k examples for 25 epochs. It’s able to get sentences it’s seen before mostly right:

Input sentence: Come alone.

Output sentence: Venez seule !

…but also sometimes wrong

Input sentence: You're not fat.

Output sentence: Vous êtes maline.

However, it has no idea what to do on items it’s never seen and just hallucinates gibberish that looks vaguely French:

Input sentence: Hello

Output sentence: Sague Tom.

Input sentence: hello

Output sentence: Elle l'aime.

(Sague is not in the training set at all, although “Elle l’aime” is the target sequence for several examples.)

Setup

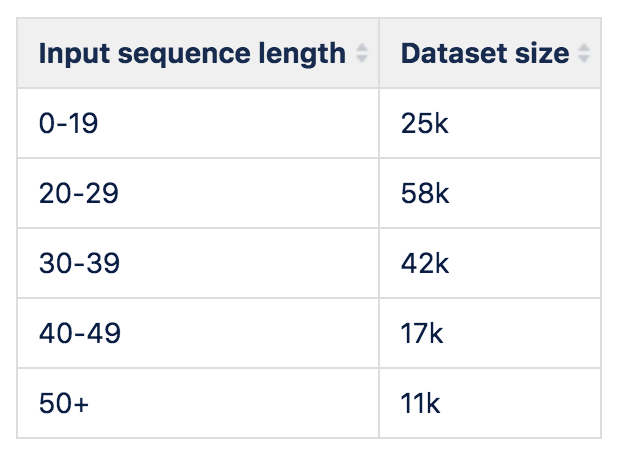

I bucketed the dataset according to the length of the input sequence. I didn’t worry too much about the length of the target sequences. There’s always going to be that one example that’s way longer than the rest, but for the most part, I would expect the target sequence length to follow a normal-ish distribution centered around some mean that grows linearly with the input sequence (and this seems to be true from looking at a couple buckets). The amount of data in each bucket goes like this:

Fig 1: how do I change the image size on Medium? This image is being upsampled. Doesn’t look good, Medium

Fig 1: how do I change the image size on Medium? This image is being upsampled. Doesn’t look good, Medium

Everything above 50 characters input is discarded, but for all the other buckets we train several models using only sampled subsets of the data available to simulate having more or less data.

The loss function used for the model is categorical cross-entropy, which somewhat makes sense because the thing the decoder is trying to predict is categorical (different tokens from the vocabulary = character set). However, it doesn’t really tell you how good the translation is. For model performance I used the BLEU score, a commonly used evaluation metric in machine translation.

Quick Recap on BLEU

BLEU can be thought of as modified n-gram precision score averaged across multiple values of n. We compare a candidate translation against a set of known references (in this context the reference would be the human translation from tatoeba that we’re using as the target output, and there may be more than one reference per item). To get the normal unigram precision, you would take each unigram in the candidate and see if it appears in a reference. The modification is that if there are multiple instances of the same unigram, we only count up to the maximum number of times that unigram appears in the reference (another way to think about this is that each time a unigram from the candidate matches a unigram in the reference, we “consume” one from the reference and cross it out, so that each unigram in the reference can get matched at most once). We then do the same for bigrams, etc. In general, you would take all of the modified n-gram precisions up to some max n, and then take their weighted geometric mean to get the final BLEU score. The default BLEU score calls for going up to 4-grams (I think there is some paper that claims this is optimal in some sense) using uniform weights, and so is called BLEU-4.

BLEU-4 is a standard in the literature so you can pretty much just go ahead and drop that in your analysis as is, except nope because geometric mean means that if any of the precisions is 0, then the whole score is 0. Because we are dealing with pretty short sequences in our dataset, it quite often happens that the 4-gram precision is 0 (sometimes the entire translation is only one 4-gram or even shorter). To deal with this problem, we can use a technique called smoothing, which basically tries to tweak the algorithm so that you don’t get such drastic dropoffs in these edge cases that happen all the time. There is a paper (which is implemented in the nltk library) that talks about many options for smoothing. I just picked one that made sense to me (smoothing_function=chencherry.method4).

Note that although we are training and translating on a character by character basis, the BLEU score is based on matches of word n-grams (not character n-grams)

One other thing I briefly explored was whether increasing the latent dimension (the dimensionality of the state vector that the encoder/decoder share) would improve the performance. I ran out of time so I didn’t train a model for every possible configuration of parameters, but I have enough to draw a simple line along one axis.

Results

Fig 3: I ran out of time so I didn’t train a model for every possible configuration of parameters

Fig 3: I ran out of time so I didn’t train a model for every possible configuration of parameters

The x-axis shows how large the training dataset was (in units of 1000s) and the y-axis is the BLEU score after 200 epochs.

This data basically allows us to naively estimate how large the dataset needs to be to train a model that can perform at a given desired BLEU score for input sequences of a given length. I say naively because I am planning to just fit a line, but you can already see that it looks like the grow is maybe sublinear so in fact you will need more data than the linear estimate suggests.

Naive Estimates That Should Definitely Not Be Believed

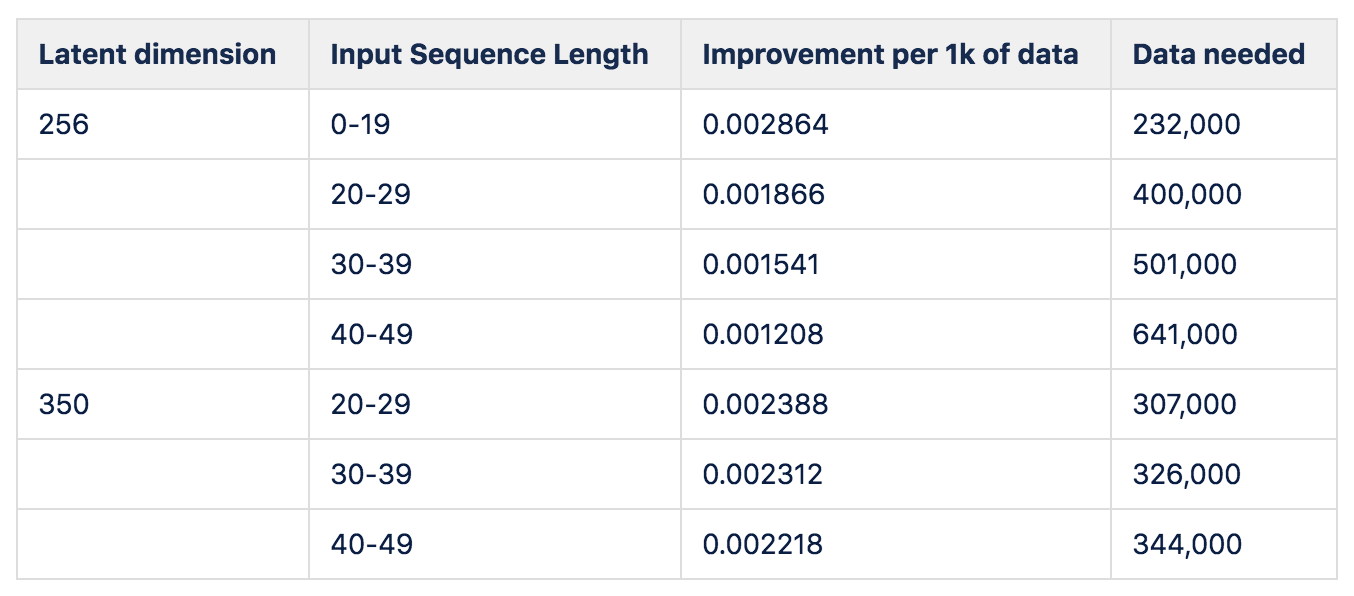

Let’s say that we are shooting for a score of 1. BLEU is always between 0 and 1, and although we wouldn’t expect even (good) human translators to hit a score of 1 (because there can be many ways to say the same thing), we want to get as close as possible. This chart tells you how much data you need to get there:

Fig C: Medium should have an insert table functionality

Fig C: Medium should have an insert table functionality

Footnote

How I created this table:

-

First, do a linear fit for each bucket using only the first three data points

-

For (latent dimension = 256, input sequence = 20–29), also do a linear fit using all data points except for the first three

-

Use (latent dimension = 256, input sequence = 20–29) to get a pegging factor for how much you need to adjust the estimates from step 1 and apply it to all the buckets

This hack is needed because as we noted, the growth seems to slow down as the dataset increases, so because we have more or less data points available depending on the bucket, so if we just straight up did a linear fit using all of the data points available, we would get a much larger estimate for the 20–29 bucket (for which we have the most data) than other buckets, and we wouldn’t be able to see the trend for how much the data requirement grows as a function of sequence length.

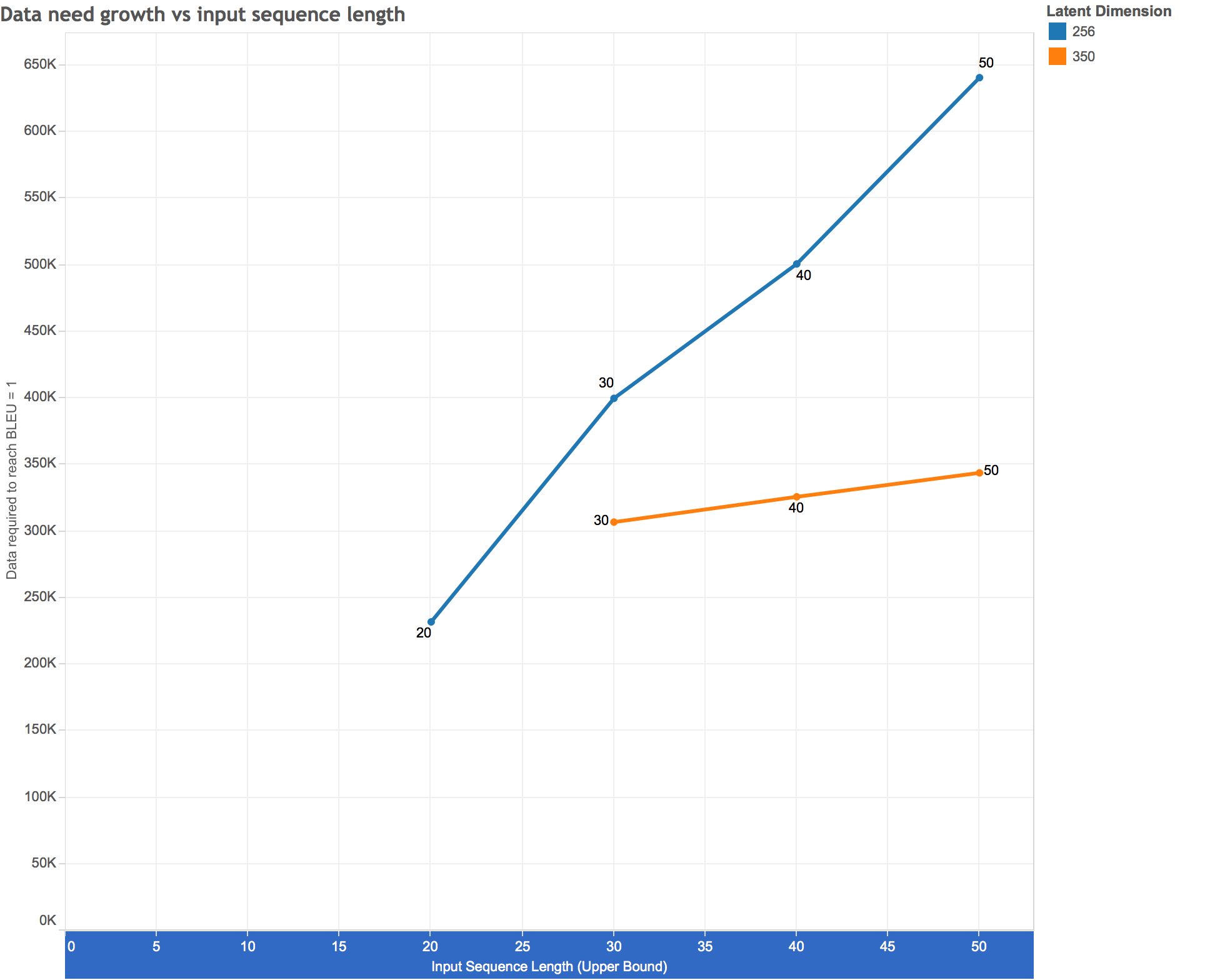

How Data Required Grows As Sequence Length Increases

We are now ready to answer the original question: how does the amount of data needed to train a performant seq2seq model grow as a function of the input sequence length?

The answer seems to be linear. Double the sequence lengths you’re interested in, double the amount of data you need to train the model. (Granted we only have 3 or 4 data points per line but it looks extremely linear to me.)

I’m not sure how much I believe the estimates themselves (it’s not clear to me that a human-level translation model can be built on a character-by-character basis even with arbitrarily large datasets), but hopefully the growth rates observed here can be extrapolated to other use cases and datasets (translation with words as tokens, text summarization, etc.).

In terms of the latent dimension, presumably there comes a point where additional dimensions actually becomes harmful (because the vector space is too large for the amount of complexity being modeled), but at least for the values we’ve investigated in this project, more is always better, even for the shortest sequences (0–20), which is kind of surprising. If the extrapolations above are to be believed, having a latent dimension of 350 gives substantial savings in terms of the dataset required (though, of course, at cost of increased computation resources).

Summary

In conclusion, we modeled the dependency of seq2seq on data as a function of input/out sequence length by training an example translation model at various different lengths and measuring the BLEU score of the output.

We found that the relationship to be roughly linear. (It’s possible that at some point the relationship becomes no longer linear, but we didn’t encounter that within the parameters of this experiment.)

This result can give you a very rough idea of how much data you will need for your seq2seq project. At Scribd, we use or have explored using seq2seq for a variety of projects, including query parsing, query tagging, and spelling correction. If working on one of these projects is something you think you might be interested in, go ahead and give us a holler at https://www.scribd.com/about/data_science