User-uploaded documents have been a core component of Scribd’s business from the very beginning, understanding what is actually in the document corpus unlocks exciting new opportunities for discovery and recommendation. With Scribd anybody can upload and share documents, analogous to YouTube and videos. Over the years, our document corpus has become larger and more diverse which has made understanding it an ever-increasing challenge. Over the past year one of the missions of the Applied Research team has been to extract key document metadata to enrich downstream discovery systems. Our approach combines semantic understanding with user behaviour in a multi-component machine learning system.

This is part 1 in a series of blog posts explaining the challenges and solutions explored while building this system. This post presents the limitations, challenges, and solutions encountered when developing a model to classify arbitrary user-uploaded documents.

Initial Constraints

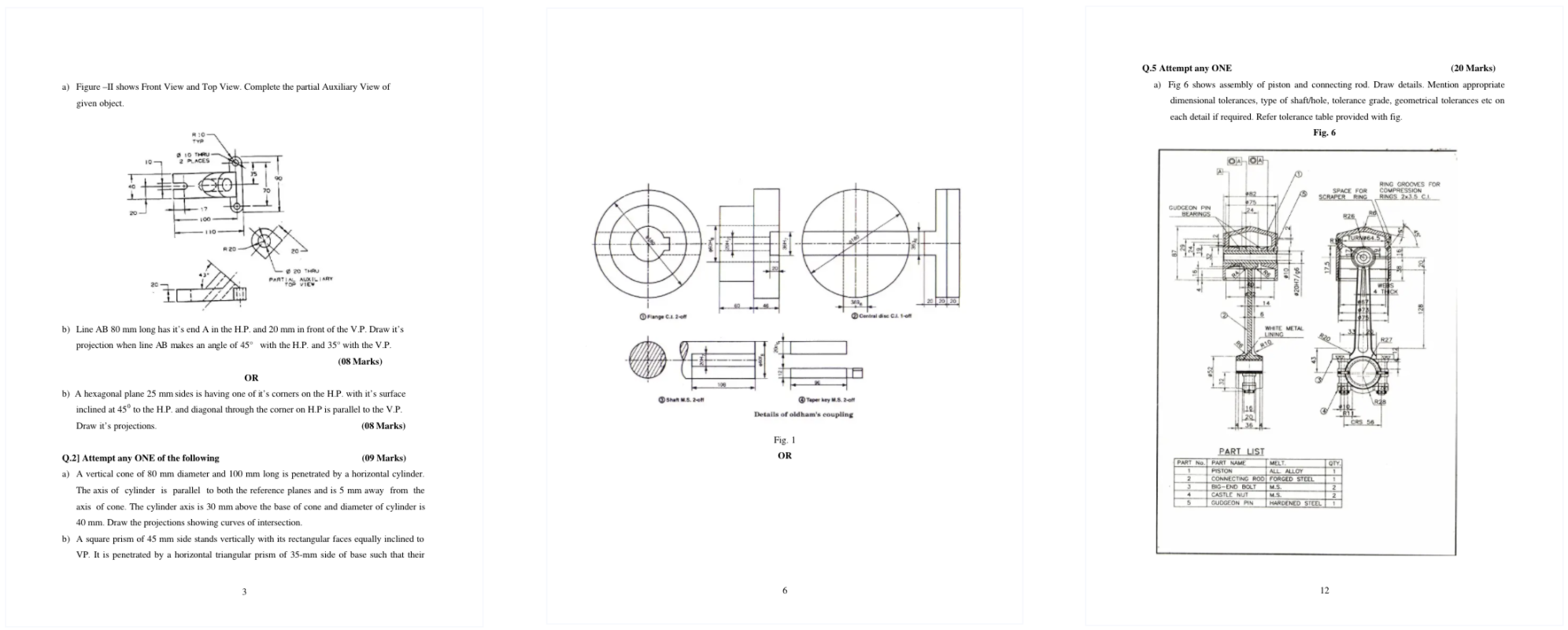

The document corpus at Scribd stretches far and wide in terms of content, language and structure. An arbitrary document can be anything from math homework to Philippine law to engineering schematics. In the first stage of the document understanding system, we want to exploit visual cues in the documents. Any model used here must be language-agnostic to apply to arbitrary documents. This is analogous to a “first glance” from humans, where we can quickly distinguish a comic book from a business report without having to read any text. To satisfy these requirements, we use a computer vision model to predict the document type. But what is a “type”?

Identifying Document Types

A necessary question to ask, but a difficult one to answer – what kind of documents do we have? As mentioned in the section above, we’re interested in differentiating documents based on visual cues, such as text-heavy versus spreadsheet versus comics. We’re not yet interested in more granular information like fiction VS non-fiction.

Our approach to this challenge was twofold. Firstly, talking to subject matter experts at Scribd on the kinds of documents they have seen in the corpus. This was and continues to be very informative, as they have domain-specific knowledge that we leverage with machine learning. The second solution was to use a data-driven method to explore documents. This consisted of creating embeddings for documents based on their usage. Clustering and plotting these embeddings on an interactive map allowed us to examine document structure in different clusters. Combining these two methods drove the definition of document types. Below is an example of one of these maps we used to explore the corpus.

We converged on 6 document types, which included sheet-music, text-heavy, comics and tables. More importantly, these 6 classes don’t account for every single document in our corpus. While there are many different ways of dealing with out-of-distribution examples in the literature, our approach explicitly added an “other” class to the model and train it. We talk more about its intuition, potential solutions to the problem and challenges faced in the coming sections.

Document Classification

As mentioned in the introduction, we need an approach that is language and content agnostic, meaning that the same model will be appropriate for all documents, whether they contain images, text, or a combination of both. To satisfy these constraints we use a computer vision model to classify individual pages. These predictions can then be combined with other meta-data such as page count or word count to form a prediction for the entire document.

Gathering Labelled Pages and Documents

Before the model training started, we faced an interesting data gathering problem. Our goal is to classify documents, so we must gather labelled documents. However, in order to train the page classifier mentioned above, we must also gather labelled pages. Naively, it might seem appropriate to gather labelled documents and use the document label for each of its pages. This isn’t appropriate as a single document can contain multiple types of pages. As an example, consider the pages in this document.

The first and third pages can be considered text-heavy, but definitely not the second. Taking all the pages of this document and labelling them as text-heavy would severely pollute our training and testing data. The same logic applies to each of our 6 classes.

To circumvent this challenge, we took an active learning approach to data gathering. We started with a small set of hand-labelled pages for each class and trained binary classifiers iteratively. The binary classification problem is simpler than the multi-class problem, requiring less hand-labelled data to obtain reliable results. At each iteration, we evaluated the most confident and least confident predictions of the model to get a sense of its inductive biases. Judging from these, we supplemented the training data for the next iteration to tweak the inductive biases and have confidence in the resulting model and labels. The sheet music class is a prime example of tweaking inductive biases. Below is an example of a page that can cause a sheet music misclassification if the model learns that sheet music is any page with horizontal lines. Supplementing the training data at each iteration helps get rid of inductive biases like this.

After creating these binary classifiers for each class, we have a large set of reliable labels and classifiers that can be used to gather more data if necessary.

Building a Page Classifier

The page classification problem is very similar to ImageNet classification, so we can leverage pre-trained ImageNet models. We used transfer learning in fast.ai and PyTorch to fine-tune pre-trained computer vision architectures for the page-classifier. After initial experiments, it was clear that models with very high ImageNet accuracy, such as EfficientNet, did not perform much better on our dataset. While it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why this is the case, we believe it is because of the nature of the classification task, the page resolutions and our data.

We found SqueezeNet, a relatively established lightweight architecture, to be the best balance between accuracy and inference time. Because models such as ResNets and DenseNets are so large, they take a lot of time to train and iterate on. However, SqueezeNet is an order of magnitude smaller than these models, which opens up more possibilities in our training scheme. Now we can train the entire model and are not limited to using the pre-trained architecture as a feature-extractor, which is the case for larger models.

Additionally, for this particular model, low inference time is key in order to run it on hundreds of millions of documents. Inference time is also directly tied to costs, so an optimal cost/benefit ratio would require significantly higher performance to justify higher processing time.

Ensembled Pages for Document Classification

We now have a model to classify document pages and need to use them to determine a prediction for documents and want to combine these classifications with additional meta-data, such as total page count, page dimensions, etc. However, our experiments here showed that a simple ensemble of the page classifications provided an extremely strong baseline that was difficult to beat with meta-data.

To increase efficiency, we sample 4 pages from the document to ensemble. This way we don’t run into processing issues for documents with thousands of pages. This was chosen based on the performance of the classifier and the page distribution in the document corpus, which empirically verified our assumption that this sample size reasonable represents each document.

Error Analysis and Overconfidence

After error analysis of a large sample of documents from production, we found that some classes were returning overconfident but wrong predictions. This is a very interesting challenge and one that has seen an explosion of academic research recently. To elaborate, we found documents that were predicted wrongly with over 99% confidence scores. A major consequence of this is that it negates the effectiveness of setting a threshold on model output in order to increase precision.

While there are different ways of dealing with this, our approach involved two steps. Firstly, we utilized the “other” class mentioned earlier. By adding many of these adversarial, out-of-distribution examples to the “other” class and re-training the model, we were able to quickly improve metrics without changing model architecture. Secondly, this affected some classes more than others. For these, individual binary classifiers were built to improve precision.

Where do we go from here?

Now that we have a model to filter documents based on visual cues, we can build dedicated information extraction models for each document type – sheet music, text-heavy, comics, tables. This is exactly how we proceed from here, and we start with extracting information from text-heavy documents.

Part 2 in this series will dive deeper into the challenges and solutions our team encountered while building these models. If you’re interested to learn more about the problems Applied Research is solving or the systems which are built around those solutions, check out our open positions!