Why LTR? (Lifetime Revenue)

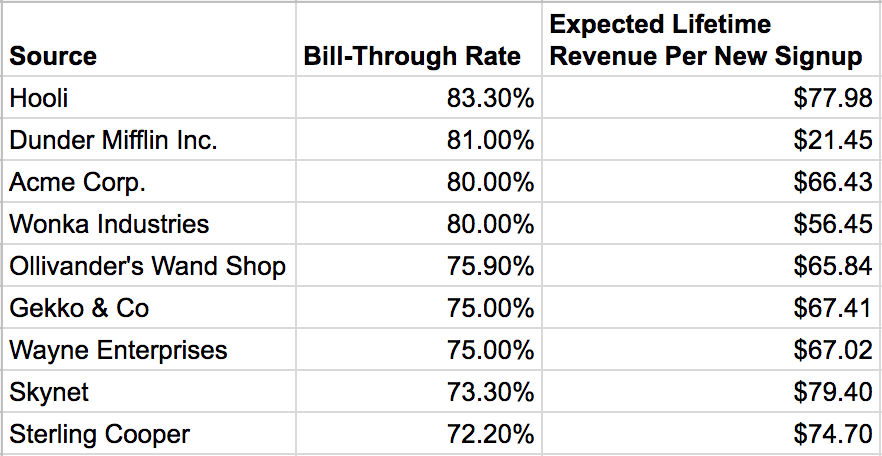

When I joined the Data Science team at Scribd, my first project was to update a dashboard that our Marketing team uses to make ad-buying decisions. For all of our acquisition sources, this dashboard displays key indicators that we use to assess the future value of a new group of subscribers like: bill-through rate(% converting from a trial to a paid subscription), 1st day cancellation, etc. While these indicators are valuable and give our team guidance on where we should be investing our marketing dollars, they aren’t explicit signals of the future value of subscribers. You can imagine a high bill through rate not resulting in a high value group of subscribers if most of them cancel after using Scribd for only 1 month.

To truly solve this problem and empower our Marketing team to make data-driven decision about their spend, we needed a way to calculate the future value of the subscribers. Enter Lifetime Revenue (LTR)! Below is a fake version of our marketing dashboard that includes our LTR column, “Expected Lifetime Revenue Per New Signup”.

Used in this context, LTR gives our marketing team clear guidance on what acquisition sources to further invest in and which to pull back on. In other contexts, LTR can help us drive strategies to better retain our high value customers and can help us understand revenue impacts from a/b tests of our product. Talk about a win-win-win!

A quick note

To not give away too much of our secret sauce, we’ll run through how our LTR calculations would work for a fake company called Bibd, the next big innovator in the monthly bib subscription delivery space (think dollar shave club BUT for baby bibs). Our hope is that this will give you some inspiration on how you can approach modeling LTR for your use case.

Making the word a better place through delivered baby bibs

Making the word a better place through delivered baby bibs

Bibd’s Business Model

It’s important to note that Bibd subscribers are billed monthly until they cancel, which means we fall into the discrete + contractual quadrant of the customer bases matrix identified in Probability Models for Customer-Base Analysis.

with an obvious edit](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/1*lx-t8crLUW7e7dw3Rz8EVw.png) From Probability Models for Customer-Base Analysis with an obvious edit

From Probability Models for Customer-Base Analysis with an obvious edit

If your business identifies with a different quadrant of this matrix, this methodology for calculating LTR will likely be interesting but not directly applicable. Keep reading though, you may just find yourself working for an awesome subscription e-reading service that starts with “Scr” and ends with “ibd” one day.

How we calculate LTR (The Mathy part)

At a high level, we here at Bibd calculate LTR for a group of subscribers by summing monthly_retention_rate * monthly_discounted_price for months 1 to n and dividing by the number of subscribers in that group. The value of n depends on what you want to consider your model’s lifetime in months, which will be 36 in the example we’ll run through (3-year LTR). How you go about defining the groups of subscribers that you’ll be aggregating over is important and you’ll likely want to follow these two guidelines:

-

Choose a set of dimensions that yield roughly even sized groups of subscribers, or at least yield an acceptable minimum number of subscribers in each group

-

Choose a set of dimensions that are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive so you avoid double counting or excluding subscribers from your analysis

Here is the set of dimensions that we chose to aggregate over. Keep in mind that your dimensions will depend on what’s important to your business in terms of variables that represent substantial variations in retention.

-

Start month (eg 2018–01)

-

Bib color

-

Baby gender

-

Acquisition source (organic or paid)

-

Payment type (eg Apple Pay, PayPal, or credit card)

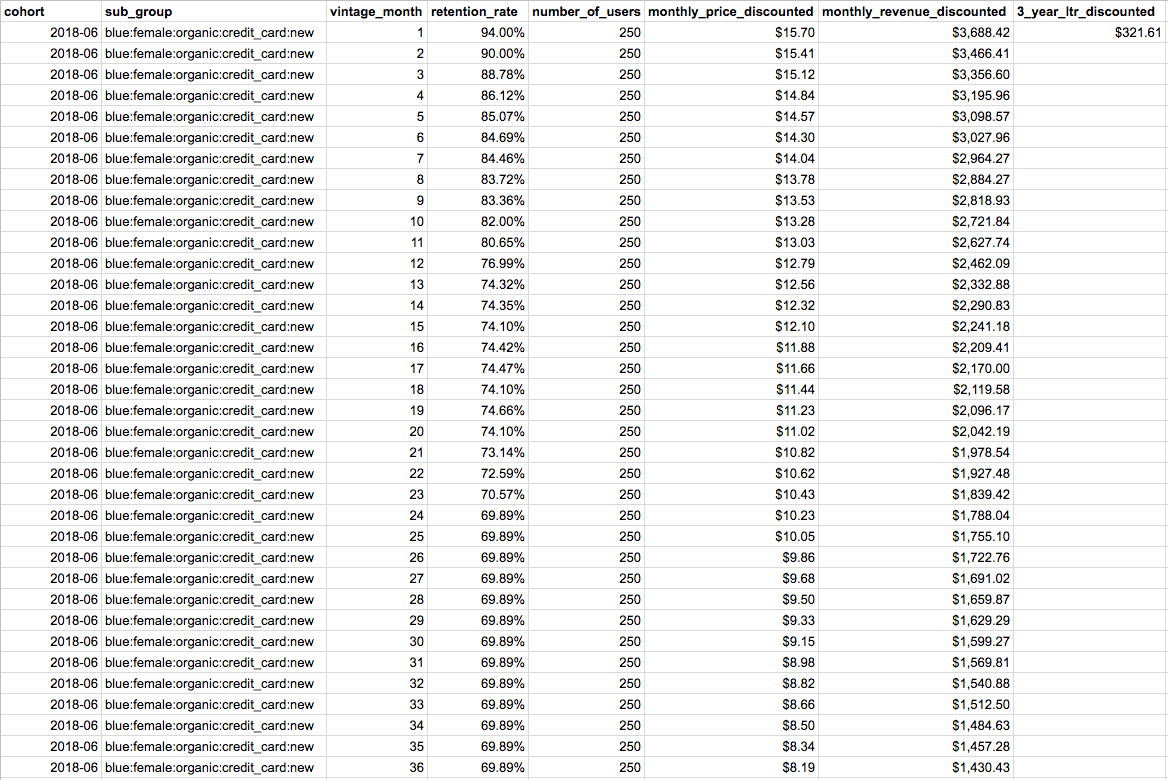

To be as specific as possible, I’ll reference data in this google sheet and run through our methodology for the group of subscribers with the following attributes:

-

Start month: 2018–06

-

Bib color: blue

-

Baby gender: female

-

Acquisition source: organic

-

Payment type: credit card

Terminology:

-

Cohort: subscription start month

-

Sub group: all of the common dimensions used to calculate LTR minus subscription start month

-

Vintage month (User Age): the number of months that a given cohort has been around. For our 2018–06 cohort, vintage month 1 is 2018–07 and vintage month 2 is 2018–08.

Here are the steps we take to calculate LTR, each of which will be broken down further below:

-

For each cohort + sub group + vintage month, calculate retention rate

-

For each sub group + vintage month, calculate retention rate…note that this is just a more general aggregation than step 1 because we’re ignoring cohort

-

Calculate a “peg rate” used to infer retention rates for months where our cohort doesn’t have data but our sub group does

-

Infer retention rates for future months

-

Sum monthly_retention_rate * monthly_discounted_price for months 1 to 36 and divide by count of subscribers in sub cohort

Breaking each of these down further…

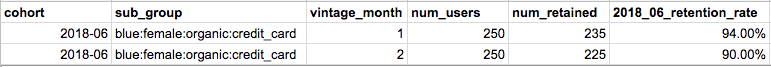

For each cohort + sub group + vintage month, calculate retention rate

Below is an example output of calculating retention rate for our example cohort. For each month that the cohort has been around (this was written when our example cohort only had 2 months of data), we’re querying for the number of subscribers who were active in each month and dividing by the total number of subscribers originally in that cohort.

For each sub group + vintage month, calculate retention rate

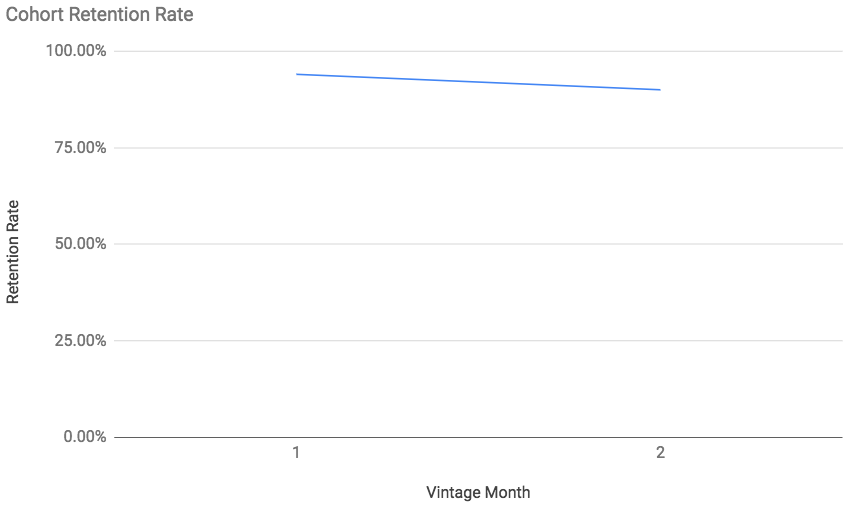

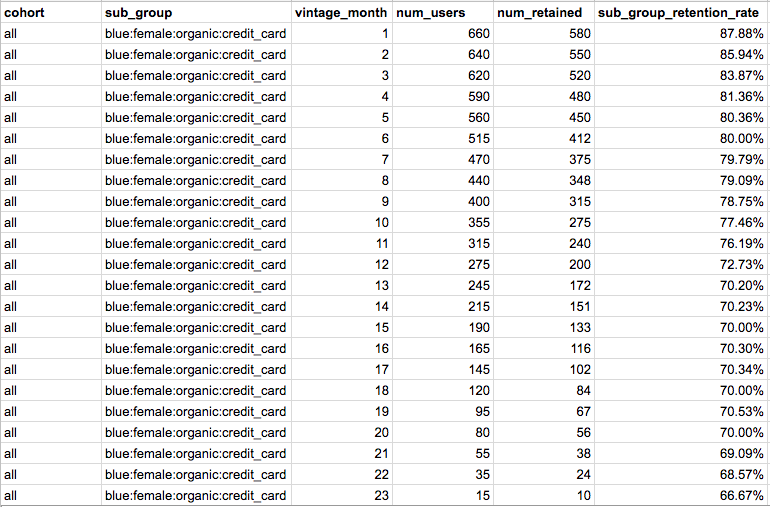

The goal of this step is the same as the last, to calculate retention rates. However, the dimensions we’re using to aggregate are slightly different because we ignore cohort, making it a more general aggregation. So in our example, we’re combining ALL of the cohorts who subscribed to blue bibs, were female, were acquired organically, and paid with a credit card to calculate our month by month retention rates. Here is an example output:

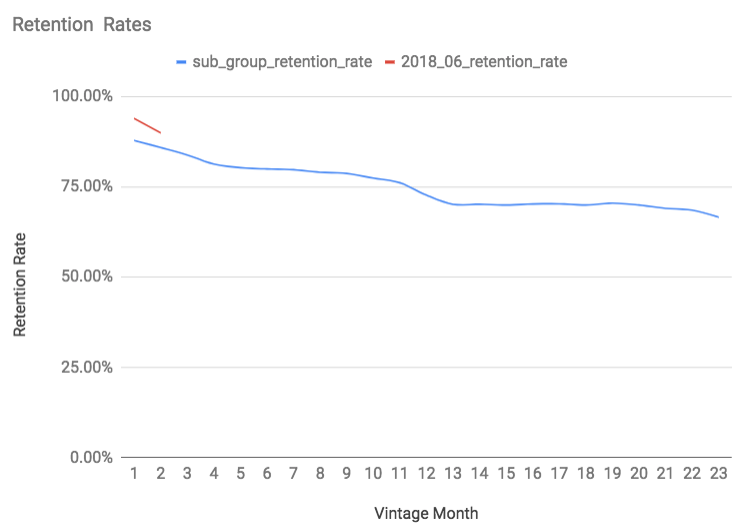

Here are our example cohort and our more general sub group retention curves graphed together:

Calculate a “peg rate”

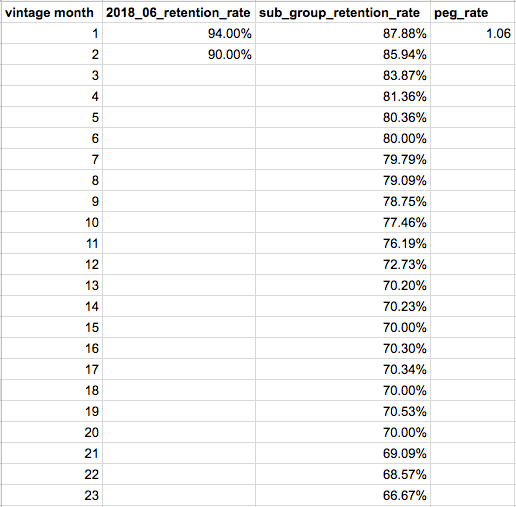

Currently, we don’t know how our example cohort will retain in vintage months 3 through 36 so it’s our job to infer retention rates to calculate 3 year LTR. The assumption our “peg rate” makes is that cohorts with the same sub group values will have similar retention curves and we can use our more general retention curve to infer future month’s retention rates for our cohort. When calculating our “peg rate”, we divide the summed retention rates for the last 5 available vintage months for our cohort (we only have 2 in our example) by the summed retention rates for the same vintage months for the more general sub group:

(0.94 + 0.90) / (0.8788 + 0.8594) => 1.06

This peg rate tells us that our example cohort is retaining at a higher rate than our more general sub group…which means we’ll assume it will continue to do so through vintage month 23!

Infer retention rates for future months

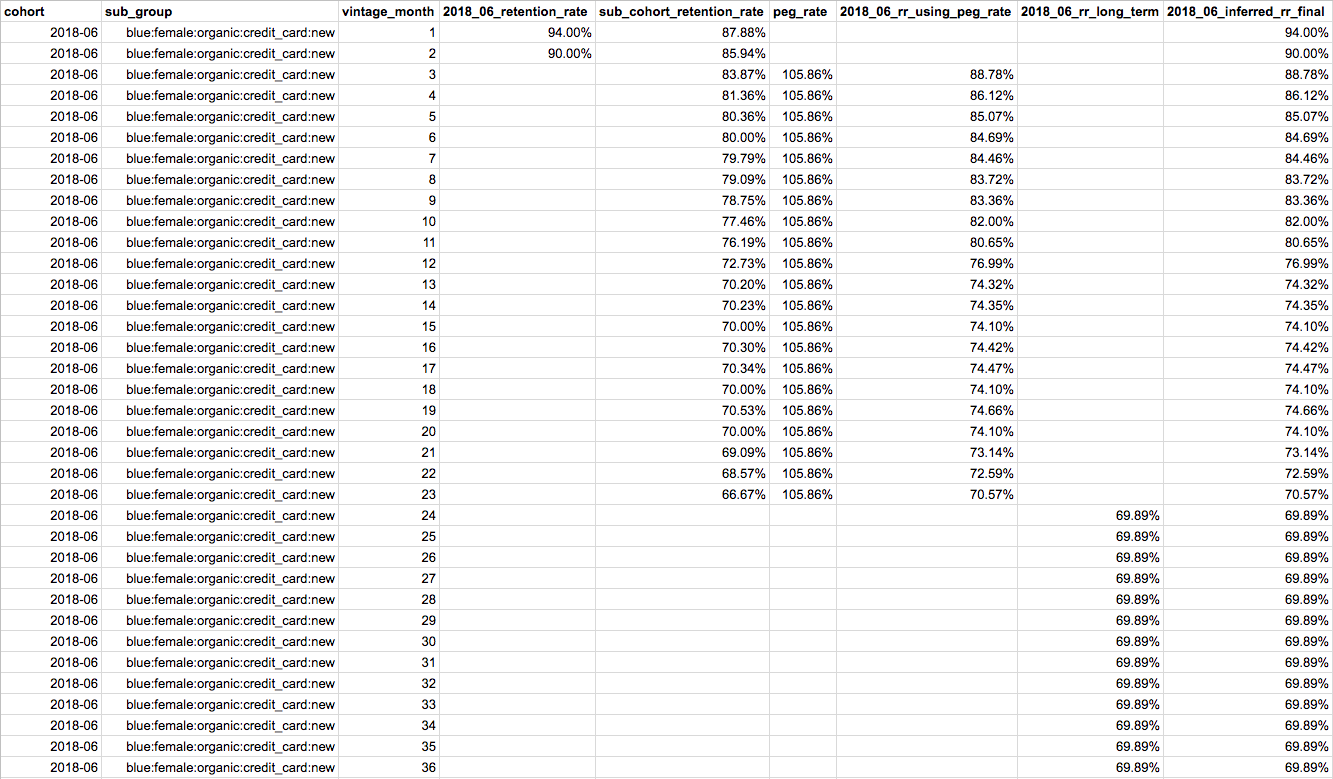

Now that we have our “peg rate”, we can use it to infer retention rates for future vintage months for our cohort. To get our inferred retention rate for vintage month 3, for example, we multiply our sub group’s retention rate for vintage month 3 by our peg rate:

0.8387 * 1.06 => 0.888

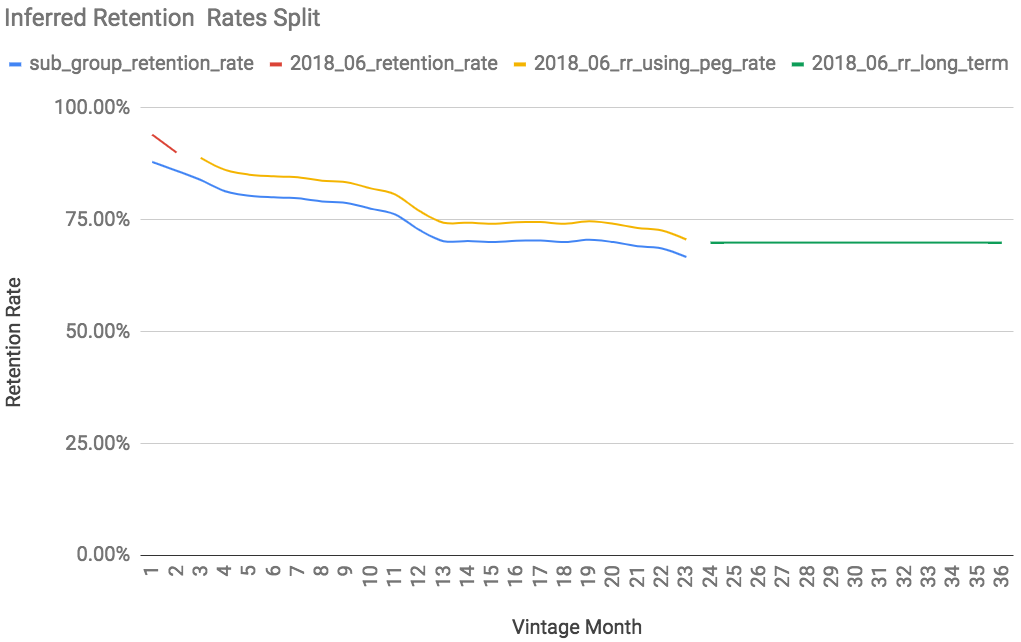

We do this for months 3–23 and when we run out of retention data for our sub group, we make the assumption that our retention rate will remain the same for all future vintage months. To get this long term retention constant, we take the average of the last 12 months of retention rates for our sub group and set that as the retention rate for our cohort for vintage months 24–36. Here is a tabular representation of calculating our inferred retention rates with the “2018_06_retention_rate” column being the actual retention data we have for our cohort, “2018_06_rr_using_peg_rate” being the inferred retention rates using our peg_rate, and “2018_06_rr_long_term” being the inferred long term retention constant.

Here is a visual for what our cohort’s final retention curve looks like, broken down by source (yellow uses our peg rate and green uses our long term constant).

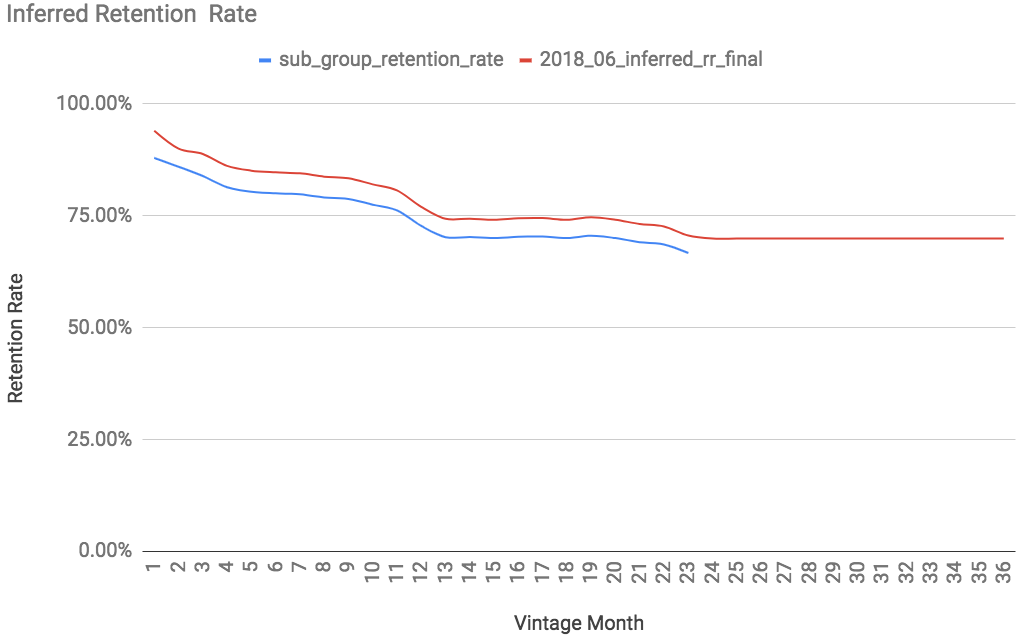

And here is a visual for what our cohort’s final retention curve looks like as one line!

Sum monthly_retention_rate * monthly_discounted_price for months 1 to 36 and divide by count of subscribers in sub cohort

Now that we have retention rates for vintage months 1–36, our only missing piece is our monthly_discounted_price. To calculate this, we assume a constant annual discount rate of 20%, which means we discount our $15.99 monthly price by 0.982 per month:

0.80 ** (1.0/12) => 0.982

So to get the discount rate for our cohort for vintage month 5, for example, we multiply the monthly discount rates up to that point:

(0.80 ** (1.0/12)) ** 5 => 0.9112

And to get our discounted price for vintage month 5, we multiply the resulting discount rate by Bibd’s monthly price:

(0.80 ** (1.0/12)) ** 5 * $15.99 => $14.57

At this point, we have everything we need to calculate our expected revenue for vintage months 1–36. For each vintage month we multiply our retention_rate by the number of subscribers originally in our cohort by our monthly discounted price. And to get our final LTR for our cohort, we simply sum those monthly revenues and divide by the number of subscribers originally in our cohort!

So what does our 3 year LTR value actually mean?

It’s important to note that our LTR predictions are averages across thousands of subscribers and that we don’t make individual subscriber LTR predictions. In other words, our prediction of $321.61 above may not be accurate for an individual Bibd subscriber…but in aggregate, this yields results we can depend on. Quantifying the error of your LTR model and deciding whether or not it’s usable is a crucial step in this type of model development and we’d encourage you to take the time to do so. The error threshold at which a LTR model becomes usable varies by company and even within the different growth stages at the same company.

Final Thoughts

In addition to predicting LTR at Scribd, we have a very similar pipeline to predict Customer Lifetime Payouts (LTP). After a subscriber has read a book on Scribd, we pay a certain amount to our publishers, so while understanding how much money we can expect a group of subscribers to pay us over time is crucial, it’s also important to understand how much we can expect that same group to cost us over time.

The Customer Lifetime Revenue problem is fascinating to me because every business must approach the problem in their own creative way. We’d love to hear how your company approaches this problem and any feedback or questions on the way we think about it.