Months ago, your friends convinced you to sign up for a half marathon. With three weeks to go, you haven’t even started training. In a growing panic, you turn to the internet for answers.

After dumpster diving through clickbait littered with pop-up ads for shoes and supplements, you land on a site that looks legitimate — no ads, clean UX, and a 20-page training manual that you can download as a PDF. And now, intrepid runner, you’re off to run the race of your life.

That *wonderful *site you went to — we make it, so you can trust our unbiased opinion.

Hi, we’re Scribd. If you need a document on just about any topic, we’re here to help. Whether you’re searching for instructions on how to set up a fly fishing rod, or how to make toast with a Hello Kitty toaster, or something that has the word “chicken” 1,500 times, we’ve got you covered.

What else ya got, Scribd?

Before you get lost in your Hello Kitty toaster manual, you should know that Scribd also offers millions of books, audiobooks, magazines, and sheet music. You can read as many as you’d like for just $8.99 a month (with a free trial!).

And this natural segue to a product plug brings us to our topic today. We’re actively working on improving our SEO for books, so that we make the first page when you search for your next read. After all, you can only have so many Hello Kitty toasters.

Yes, the Hello Kitty toaster is a very real thing

Yes, the Hello Kitty toaster is a very real thing

How we increased traffic to our book pages

Generally, the first step to getting a page ranked higher by a search engine is to make sure that it knows your page exists. Important pages are re-crawled often, which means search bot visits is the initial metric you’ll want to look at.

Our plan was to increase the bot visits to book pages, which we hoped would ultimately drive more search traffic. We did this by linking to books on our document pages (for example, this handy toaster oven cookbook). That way, when a bot crawls a document page, they also explore the linked book pages. As search engines explore the associated book pages, we hypothesized that it would lead to a higher page rank, more traffic, and more sign-ups for these book pages.

Running a non-random SEO test

Here’s what makes this hard to test: the links we want to put on the document pages aren’t random. We want to show relevant recommendations, so we use the category data that we have about the document, and link to books from the same category.

That means that on the Hello Kitty Toaster *page you’ll only see recommended books page for related topics like *Toast and AC Power Plugs and Sockets. We can randomize which categories we treat or keep as control, but we can’t completely randomize at a book or document level, even though we ultimately care about the document and book level metrics.

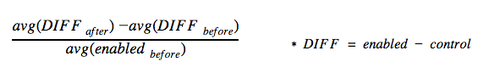

We designed our test to use pre and post analysis, per this blog from Pinterest on SEO experiments. The key formula they use is here:

If the test were randomized at the document level, some of the terms would simplify and reduce to the same formula of lift we normally use. Notice that in a randomized test the avg(DIFF before) would be 0, and assuming we don’t have big problems with seasonality, avg(enabled before) is roughly the same as avg(control after).

How a non-random test works

It doesn’t make me happy that that this experiment isn’t randomized at the document level, but in this case it was a necessary part of what we wanted to test. If you can randomize at the user or page level you should.

In this non-random case, even with a randomly split set of categories we may find that the treatment and control groups differ. The category AC Power Plugs and Sockets might never be able to balance out more popular categories. This formula helps us deal with some of the inherent differences between our treatment group and control.

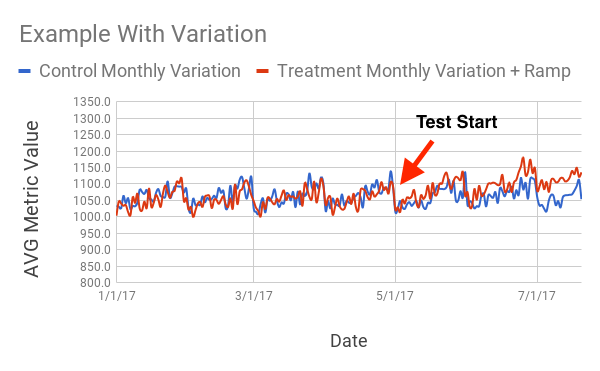

Of course, in reality we won’t be able to quickly glance at a line going up-and-to-the-right to make decisions. A more realistic example might look like this:

Solving for non-randomness (via bootstrapping)

With real data, it is more difficult to figure out if lifts are statistically significant. Anyone with a calculator can compare ratios of sums and make estimates — what makes a computation like this legitimate is also having a reasonable idea of the error in the estimate.

It was important to give statistical significance along with these results. The methodology Pinterest used was *conveniently *left out of their post, so we wanted to share how we solved this problem.

Let’s get technical

To find out where an observation lies in a distribution, the first question to ask is: What is an observation? Here it is not a day — or even a sum over some days — it is a pre-aggregated average of the difference in metrics.

In our case, the metrics we aggregate are over a 75-day period. That term in the formula AVG(Diff after) is measuring a single observation (so n = 1, not 75). This aggregation means we can’t compute standard deviations on our samples the way we normally would.

In order to disprove the null hypothesis here, we need to understand on what distribution this observation should exist. We’ll need a whole bunch of pre-aggregated 75-day averages, but it is not obvious how to get those observations. It doesn’t make sense to keep taking chunks of data further and further back in time for many reasons. The most problematic are: (1) many of the metrics were implemented within the last year, and (2) documents and books are relatively new to our site and we don’t have an infinite history.

So without an infinite set of data, what can we do to get a good sense of the distribution that we are pulling this observation from? This is where the bootstrapping comes in. You can read more about why this works here and see how it is computed here:

How bootstrapping solved our problem

This bootstrapped distribution allowed me to compute a p-value for the post-test observation. I ran a few simulations to see if there was a right number of bootstrapping samples to use. Remember, my ultimate goal is not to compute the exact p-value but to answer the question was this 75-day aggregate statistically significant?

I repeated the bootstrap process with different numbers of bootstrapped samples from 5000 to 10,000. While the p-values changed slightly, the decisions I’d make about whether to take the results seriously didn’t change as I varied the number of samples, so I went with 10,000 samples.

One side effect is that setup isn’t compatible with multiple concurrent experiments. We are doing our best to avoid this type of experiment in the future and to instead do experiments where the randomization is at the document and book level, but it is nice to have this method in our back pocket.

Where do we go from here?

We wanted to figure out a way of running a non-random test while still teasing out causal differences against a black-box algorithm (thanks, Google). This is how the real world of A/B testing works, 🤷.

To get out of this quagmire, we did our research, collaborated as a team, and came up with a bootstrapped method that lets us come away with results that can measure the improvements Product is testing to drive more SEO traffic.

For those SEO teams that crave a semblance of randomized testing and statistical significance, there is light at the end of the tunnel. We wanted to give you a flashlight to find it.

And if you need a comprehensive document about how to work that flashlight, come back to Scribd anytime. Maybe, just maybe, you’ll find a book that you like too.