Introduction

I can remember a time in middle or high school when the goto service for locating things on the internet was Ask Jeeves. We even had a tutorial on how to properly search, including when to use quotes and other special characters in order to get the most relevant results. The days of ‘query engineering’ are almost a thing of the past, made obsolete by Google’s ability to almost intuitively know what we are actually hoping to find. For better or worse, Google has trained us to expect great results with a simple set of keywords, malformed questions, and careless spelling. The last point is something I would like to discuss in a bit more detail, and how we at Scribd attempted to solve it using neural networks.

Unlike Google, our search traffic is in the hundreds of thousands of queries per day, not billions, so it can take us some time to amass enough statistics on common misspellings in the search queries that we receive. This statistical machine learning approach is how Scribd, and I’m guessing many other companies, handle this at the moment, but we started to wonder whether or not we could build a generic model that could be proactive instead of reactive. Meaning, can we start to correct spellings on the fly, for all words, instead of waiting for the statistics to roll in.

In the next few sections, I will briefly introduce seq2seq and then I will highlight two similar approaches and the pitfalls/shortcomings of each. In addition, I will give some speculative ideas as to how we might improve upon these first attempts.

Brief Introduction to seq2seq

Both of the models described below were implementations of a seq2seq model. There are already a significant number of blogs and talks out there about seq2seq, and I would like to recommend a few and briefly highlight how it works (at a high level). I really loved the talk by Quoc Le [1] where he describes in great detail how to conceptually think about seq2seq as well as give some excellent examples of where this model works well. For more implementation details, I found [6] pretty useful for understanding the underlying network.

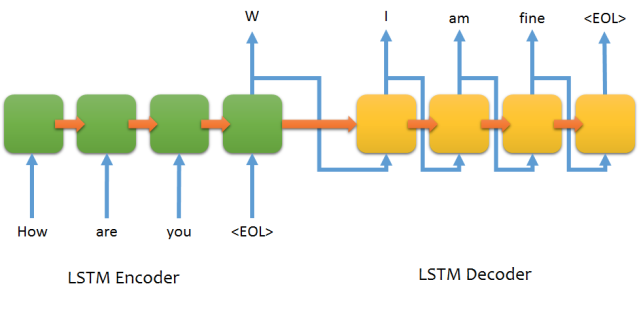

For applications, in general, if you can form your problem into an input sequence and an output sequence that you want to predict, seq2seq is likely a good approach. The basic setup is an encoder and a decoder, which consist of memory cells (LSTM/GRU) that help the network to remember long sequences. These cells differentiate them from vanilla RNNs, *which typically do poorly when the sequence increases in length. *A simple example architecture is given below:

In the example above, you can see that the basic input to these models will be a sequence of some sort (in the example, words) with the end having a special key (in this case

It’s easy to see how this can be used for translation, where your target is a different language, or for spelling corrections, where your target is the correctly spelled word.

First attempt: Deep Spell

I want to thank the author of the Deep Spell [2] blog for inspiring the idea and giving us a great starting point. I was really blown away by the quoted 95.5% accuracy that Deep Spell had achieved after only a few days of training. Surely this was the answer to all my problems! And he published his code [3], what a great guy!

So, like a good student, I downloaded the code, read through it to understand the pieces and how it worked, downloaded the test data mentioned in the blog post [2] and ran it. After about a day, I started to get nervous… why wasn’t I getting into the 90% accuracy range? So I reached out to my internet-mentor and asked for clarification [4]. I showed my training / validation curves for loss and accuracy and asked for some clarification.

Given that I’m very new to deep learning, I assumed I was doing something incorrect, however it turned out that the quoted accuracy achieved on the blog post was done with a private dataset. Bummer, but that’s fine, I decided to press on and manufacture my own dataset and steal the meat of the code found in [3] (this model has been posted below in a snippet). The model architecture was exactly the same, only this time I used my own dataset pulled from Scribd’s data warehouse which contained a list of author names and titles of books. I then randomly injected noise (or misspellings) into words, by either omitting, adding, or changing letters. Examples of each edit would be:

-

Character omission — “po er systems”

-

Character removal — “poer systems”

-

Inserting whitespace — “pow er systems”

-

Duplicating a character — “poweer systems”

-

Incorrect character — “powar systems”

The maximum number of allowed edits was 3, and I used a random number generator to decide how many to incorporate for each phrase. Input into the model was tokenized, for example, “margaret atwood” would be inserted into a fixed length vector like [20,1,5,2,1,5,8,10,27,1,10,13,15,15,17,0,…,0], where the whitespace between the words also is included as a token. This vectorization was done for both the source (misspellings) and the targets (correct spelling). It was then reshaped into a M x N matrix where M is the length of the vector and N is the number of tokens. In this case, each row will have either a 0 or 1, indicating whether or not that character is present.

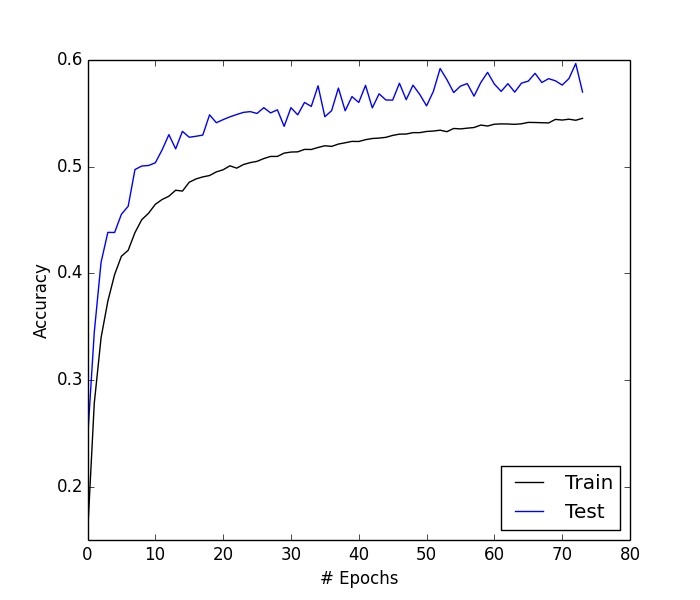

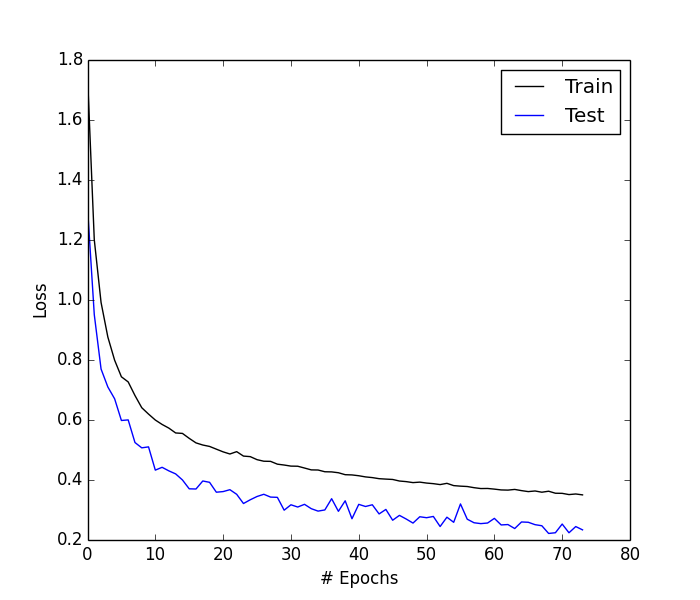

This was used to train the model for nearly a day, where I ran a total of 92 epochs (before killing it) with a batch size of 200 and 1000 steps per epoch. Much to my surprise, I hit close to the 90s for accuracy and loss looked good as well!

Had I constructed an awesome dataset? Was there some unseen bug in the previous dataset or preparation scheme? I honestly don’t know, but after I started to look at some of the predictions, I realized something wasn’t right. What I found was that the model either wasn’t adding any correction at all, or it was adding in mistakes to words that were already fine. This led to the second discovery during this process: what does accuracy actually mean?

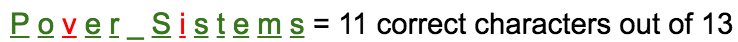

In Keras, when the loss is categorical cross-entropy and your target metric is accuracy, it’s actually looking at the average accuracy per input, then averaged over the entire dataset to give a final number. So if you misspelled the title of “Power Systems” as “Pover Sistems” your accuracy would be 84%, since you got 11 / 13 characters correct:

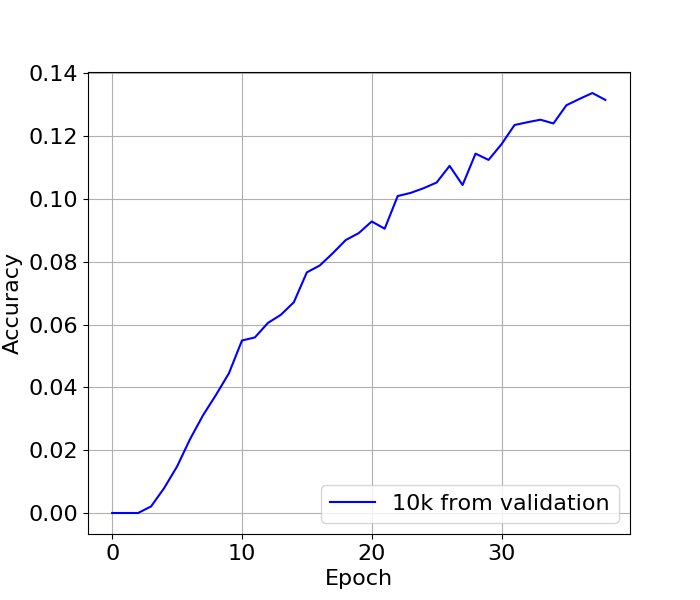

But who cares about that accuracy?! I want to know how often I get back to the right word. If I look at that, it’s terrible:

It tops out around 13%, but at least it is not at a plateau yet, so it could continue to get better. I stopped exploring this method because while this was running I found another seq2seq implementation that had some more fancy pieces included, so I pressed onward from there.

Second Attempt: OpenNMT

OpenNMT [5] stands for “open neural machine translation”, which is quite a mouthful. Neural machine translation is an exciting field trying to solve the problem of translating between languages, and the ‘open’ part simply describes that the code is open source, and has a receptive development group around it. In fact, I was able to implement a new feature [7] to translate at each epoch, something that was already on the feature request list. While my contribution wasn’t directly incorporated, it definitely got the ball rolling, so I consider this an open source contribution through nagging :-) Anyway, it’s a great package that is very easy to steer based on a configuration file where you can set various parameters, including what type of model, how you want attention to be handled, etc.

In order to run this, I had to slightly modify the input data to get it in the right format that OpenNMT could understand. Thankfully, this takes as input raw text, and evaluates to text, so it’s not too difficult. The model expects to receive words where your input is in your start language (eg. English) and your output is in your target language (eg. Chinese). The trick to make this work for spelling is to treat each character as a word, and to give whitespace a unique character. So “margaret atwood” became “m a r g a r e t _ a t w o o d”. And that’s it basically, you’re ready to train.

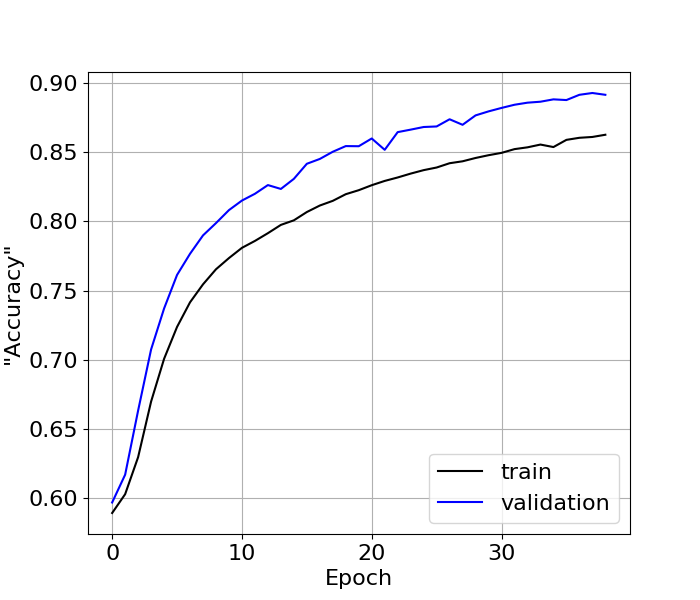

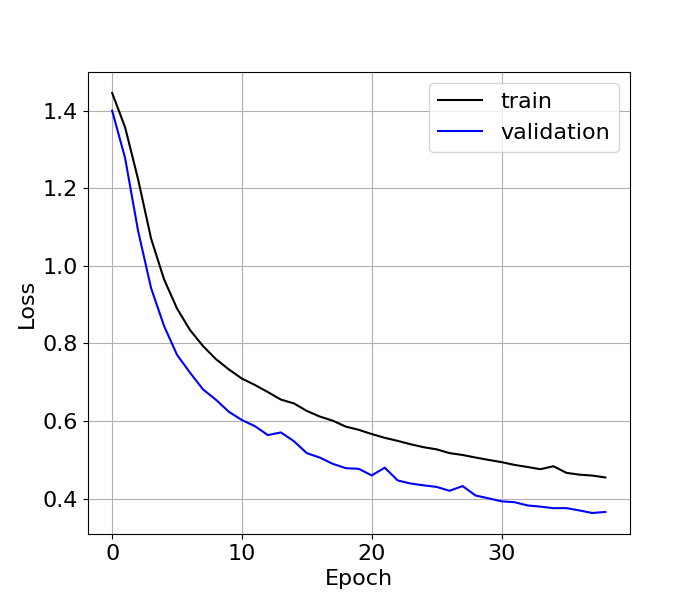

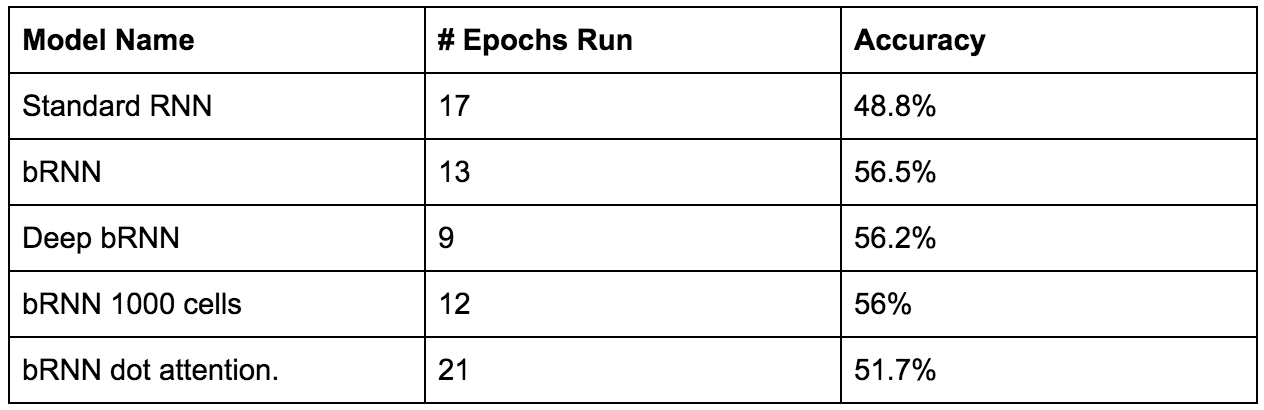

For our tests I tried a few different model structures including a basic RNN, a bidirectional RNN (bRNN), a deep bRNN, a bRNN with more cells, and a bRNN with a different attention mechanism. OpenNMT does give loss and perplexity, but these metrics still suffer similar to accuracy mentioned in the previous section, so I am just quoting the final accuracy that I trained the models too (along with the number of epochs). All models used LSTMs with 500 cells (unless otherwise noted) and the general attention mechanism in OpenNMT is used.

Not bad, much better than 13%! Here are some examples of those that it got correct:

-

Mistake reuniting dhe divided statess ameeica Guess: reuniting the divided states america

-

Mistake pygmalion urld classics unabtidged Guess: pygmalion world classics unabridged

-

Mistake rcg nna bethory Guess: regina bethory

Looking at some failed cases, we can see that some words are difficult (eg. names) and others there just isn’t enough information:

-

Truth: colonel tracey goetz Mistake cplonel tracey gietz Guess: colonel tracey gietz

-

Truth: fuan kang Mistake fuan keng Guess: ryan king

-

Truth: make good pub Mistake nake good ub Guess: make good club

-

Truth: birthday wishes smitten novella Mistake birthday wishes smutten novellaa Guess: birthday wishes smutten novella

This showed that sometimes, it doesn’t get it back to the right word, but it does correct to an in-vocab word. If instead I look at the before and after percentage of in-vocab words when compared to the total words used I find a jump from 56% before to 91% after! So it is correcting a majority of the words to something, but that something isn’t always right.

Parting thoughts

In the end we couldn’t use this in production because the direct accuracy is what we cared about the most. It actually reminded me of one of my professor’s comments from grad school, “We are not searching for an answer. We are looking for the answer.” So for the time being, we haven’t found the answer, and we continue to be reactive with statistical machine learning.

Even though we didn’t arrive at a production ready model at the end, we learned a ton. Neural spelling corrections do seem possible, and that’s evidenced by the 56% accuracy in correcting whole phrases and the jump to 91% total words in the vocabulary from 56% at start time. The next step would be to try to add some contextual information so that when the model sees ‘ub’ and is preceded by ‘make good’ it should know to pick ‘pub’ instead of ‘club’.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G5RY_SUJih4&feature=youtu.be

[2] https://medium.com/@majortal/deep-spelling-9ffef96a24f6

[3] https://github.com/MajorTal/DeepSpell

[4] https://github.com/MajorTal/DeepSpell/issues/11

[6] http://suriyadeepan.github.io/2016-12-31-practical-seq2seq/

[7] http://forum.opennmt.net/t/save-validation-translations-at-each-epoch/286

Pass 1 model in Keras:

Pass 2 Config File