Scribd has been in an agile transition for two years now and as we iterate and improve with company growth we have needed to reevaluate a number of practices such as utilizing story points.

Story points in agile are a way of estimating how much work something is. They are deliberately not exact functions of difficulty and time. You will never know all the complications when you start a project. Even something as simple as making dinner can get tripped up by a missing ingredient or a dirty pot, so too can software projects. Our first foray into story points was done with a small group of folks who had a good understanding of the practice and its implementation. When rolling story points out across the broader organization we made a couple mistakes, namely that we didn’t socialize that change both across the organization and upwards.

It can be very easy to say “oh, that’s 8 points” in a planning meeting, but that’s hard to translate into a meeting where we cover all the projects currently in flight, especially when trying to arrive at a target and actual done date for the project or task. We had a tendency to get attached to those dates, making plans across the organization. Then when a team would slip on that translated schedule, everybody would get upset!

The team would be upset because they knew that “8 points” was an estimate that accommodated their internal understanding of a period of time. Management would be upset because things slipped from their translated schedule which was itself based on a global translation of story points into time.

(source)

(source)

So..story points got banned from the management meeting. Project managers could then only speak to deadline dates and added language that mentioned things like ‘best estimate’ and ‘could slip’ to hedge around the fact that software development isn’t an exact science. We still talked in story points in our team meetings but it was a verboten term outside that space which led to its own tensions.

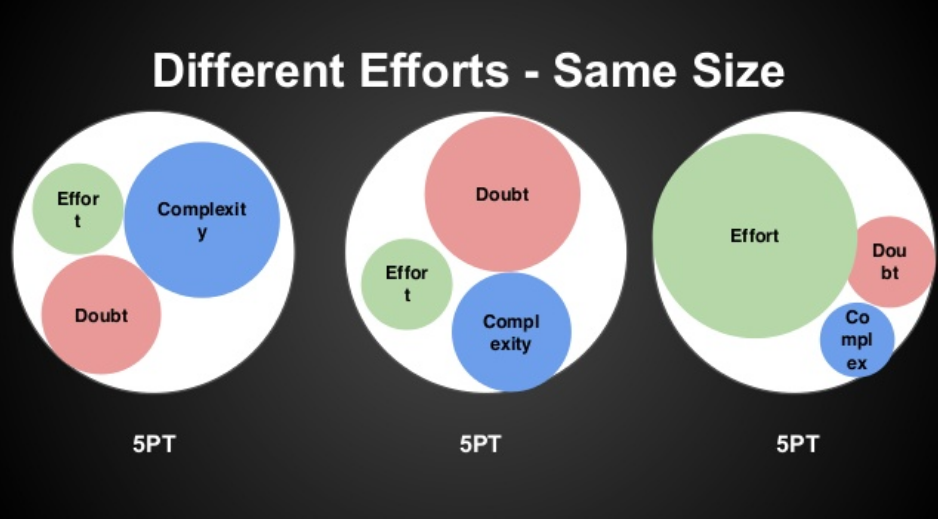

One of the other reasons story points got banned was the nature of the imprecision. Yes, points should be specific to the team but our velocity was completely unpredictable from team to team. Sometimes it would be 20 points and others 50. Regression passes were sometimes included and pointed, sometimes they weren’t. It started with a team of more junior developers and QA that had one of the aforementioned velocity issues. We asked them how big a 3/5/8 was and got a different answer from each of them. We had found the underlying problem that had given story points a bad name!

It was time to go back to basics. We had a “story pointing workshop” with that team. The team already had strong communication and had a safe space, a retrospective, to talk through the issue of why their understanding was all over the map. Some of it was because they were more junior and were less likely to know where the problems were in the code base, but some of it was because we had just assumed that everyone knew what a 5 might entail. An hour later we had a white-board covered in notes with items under each number in the Fibonnaci sequence. Items that included things from each of the developers, QA and the squad lead (in this case a senior developer). We did it again with the entire mobile QA team, sharing some of the findings after we first did the brainstorm fresh, sharing where that team had seen points falling. It turned into a wiki page that was shared within the project management team, and it spread from there.

(source)

(source)

We were clear throughout this process that points were still team specific and that none of this was to be taken as hard and fast rules but it gave teams a place in which to start the conversation and have common ground. We don’t want to make it sound like all the teams were terrible at making story point estimates, or bad having reliable velocity, but the variability often exceeded 10%. Larger variance made it hard for management to show trust in our date estimates. With some common guidelines, it became easier for teams to have more accuracy, which led to more trust in deadlines, which ultimately gave us a way to talk about story points again.

When the deadlines shifted to being reliable within a day or two, the conversation wasn’t as charged since somebody could show the good breakdown on the work, which was also reflected in Jira. We operate a project lifecycle that starts with a product brief, goes through design iterations, and then goes into story breakdown and sizing. Only after those steps are done do we “put hands on keyboard” and start writing software, usually with pretty solid estimates. It turns out people really do need time to think through the problem before solving it!

Our approach isn’t perfect of course. We still have spots of tech debt and brittle code. We will always have people who under or over estimate work, but that’s why we use story points.

The initial reaction to story points was justifiable, but we continued to iterate on the problems we ran into with the original implementation of story points. Finally, by bringing up the concept of “velocity” and demonstrating how teams were getting more reliable in their estimates with story points, we were able to show management that the method was worth trusting.