We are using Apache Kafka as the heart of more streaming applications which presents interesting design and development challenges: where does the data producer’s responsibilities end, and the consumer’s begin? How coupled should they be? And of course, can we accelerate development by building them in parallel? To help address these questions, we treat our Kafka topics like APIs rather than cogs in a single pipeline. Like RESTful API endpoints, Kafka topics create a natural seam between development of the producer and that of the consumer As long as producer and consumer developers both agree on the API contract up front, development can run in parallel. In this post I will share our stream-oriented development approach and the open source utility we developed to make it easier: kafka-player.

APIs for Topics

Perhaps the most important part of developing producers and consumers in parallel is creating those “API contracts.” Kafka topics provide a persistent storage medium where producer applications write data to be consumed by other applications. To consume data from a topic appropriately, applications must know how to deserialize the messages stored on these topics. We formalize the data formats shared by producers and consumers by defining message schemas for each of our topics. We happen to serialize our messages as JSON, and we use a yaml formatting of JSON schema to formalize our shared schema definitions, giving us the necessary API contract to enforce between producer and consumer.

The snippet below shows a general version of what one of these message schemas look like in yaml. This comes from one of our real schemas but with all of the interesting fields removed.

---

"$schema": http://json-schema.org/draft-07/schema#

"$id": some-topic/v1.yml

title: Some Topic

description: Event sent by ...

type: object

properties:

meta:

description: Metadata fields added by systems processing the message.

type: object

properties:

schema:

description: The message-schema written to this topic by producers.

type: string

producer:

description: Metadata fields populated by the producer.

type: object

properties:

application_version:

description: The version of the producer application.

type: string

timestamp:

description: An ISO 8601 formatted date-time with offset representing the time when the event was handled by the producer. E.g. 2020-01-01T15:59:60-08:00.

type: string

format: date-time

required:

- version

- timestamp

required:

- producer

uuid:

description: A unique identifier for the event.

type: string

user_agent:

description: The user agent header of the request.

type: string

# ... - All the other fields

required:

- meta

- uuid

And an example message that satisfies this schema would look something like:

{

"meta": {

"schema": "some-topic/v1.yaml",

"producer": {

"application_version": "v1.0.1",

"timestamp": "2020-01-01T15:59:60-08:00"

}

},

"uuid": "3a0178fb-43e7-4340-9e47-9560b7962755",

"user_agent": ""

}

With the API contract defined, we’re one step closer to decoupled development of producer and consumer!

Working with a Streaming Pipeline

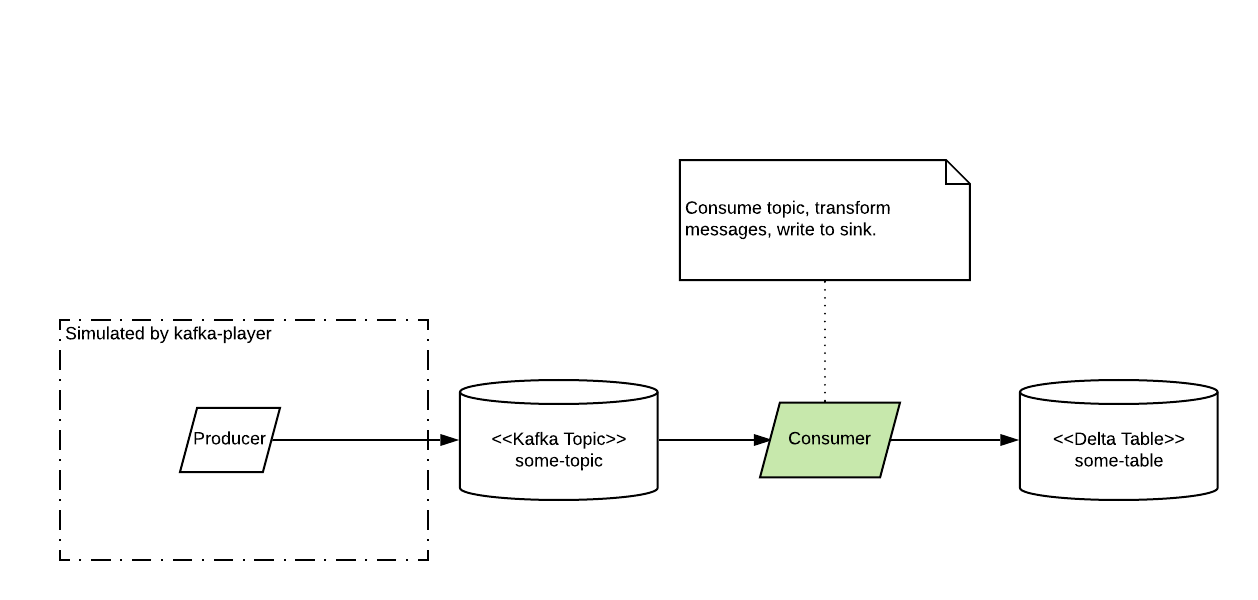

For many of our new streaming pipelines, a Kafka topic is the first data sink in the pipeline. The next application in the pipeline reads the topic as a streaming source, performs some transformations and sinks to a Databricks Delta Lake table.

The effort to build applications on each side of those topics may be significant. In one of our recent projects, we had to implement a new Docker image, provision a number of new AWS cloud resources, and do a considerable amount of cross-team coordination before the producer could even be deployed to production. The work on the consumer side was also quite significant as we had to implement a number of Spark Structured Streaming jobs downstream from the topic.

Naturally we didn’t want to block the development of the consumer-side while we waited for all the producer-side changes to be implemented and delivered.

Dividing Labor

Fortunately, since we define our message schemas beforehand, we know exactly what the data should look like on any given topic. In that recent project, we were able to generate a large file containing new-line delimited JSON and then do full integration testing of all components downstream of the Kafka topic before any production data had actually been written by the producer.

To help with this, we built a very simple tool called kafka-player 1.

All kafka-player does is play a file, line-by-line onto a target Kafka topic.

It provides a couple of options that make this slightly more flexible than just

piping the file to kafkacat. Most notably the ability to control

message rate.

When we were just getting started in the local development of our Spark applications, we pointed

kafka-player to a local Kafka Docker container and set message rate

very low (i.e. one message every two seconds), so we could watch transformations and aggregations

flow through the streams and build confidence in the business logic we were implementing.

After we nailed the business logic and deployed our Spark applications, we pointed kafka-player at our

development MSK Cluster and cranked up the message rate

to various thresholds so we could watch the impact on our Spark job resources.

Future Extensions

Controlling message rate has been a very useful feature of kafka-player for us already, but the

other nice thing about having kafka-player in our shared toolbox is that we have a hook in place where we can

build in new capabilities as new needs arise.

For our recent projects, we have been able to generate files

representing our message schemas pretty easily so it made sense to keep the tool

as simple as possible, but this might not always be the case.

As we mature in our usage of JSON schema and encounter cases where generating a large file representing our

schemas is impractical, we may find it useful to enhance kafka-player so that it can generate random data

according to a message schema.

Deployment tooling may also be on the horizon for kafka-player. The level of integration testing

we’ve achieved so far is helpful, but with an image and some container configuration,

we could push multiple instances of kafka-player writing to the same topic to a container

service and create enough traffic to push our downstream consumers to their breaking points.

Most of our data workloads at Scribd are still very batch-oriented, but streaming applications are already showing incredible potential. The ability to process, aggregate, and join data in real-time has already opened up avenues for our product and engineering teams. As we increase the amount of data which is streamed, I will look forward to sharing more of the tools, tips, and tricks we’re adopting to move Scribd engineering into a more “real-time” world!

-

kafka-player is a simple utility for playing a text file onto a Kafka topic that has been open sourced by Scribd. ↩