How Scribd’s web team transitioned from a ten year old legacy code solution to a fully modern tech framework without starting from scratch.

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/search/photos/light-tunnel?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/8544/1*_2kL4FViZJmj-QIT51NnLQ.jpeg) Photo by Ryan Wallace on Unsplash

Photo by Ryan Wallace on Unsplash

When I started on Scribd’s web team two years ago, Scribd’s web application was written predominately in Fortitude (a Ruby templating language) and Coffeescript (a Ruby-like language that transpiles into Javascript).

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/search/photos/frustrated?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/10944/1*uXReRq6bj50Y0xIhTm9PYg.jpeg) Photo by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash

Photo by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash

It wasn’t difficult to pick up Coffeescript, which actually predates several of the features added to ES6, but it made developing slower as a newcomer, due to its rather unusual syntax. It was also frustrating to know that I was learning and working in a language that was barely maintained by the community and had lost much of its developer following as attention shifted towards more modern languages. Our implementation of React was especially vexing, as it relied on a custom helper to translate between Coffeescript and the ES5 version of React, that needed to be continuously updated if we wanted to take advantage of newer React features.

So, when I was tasked with building the redesign of our cancellation flow, I took that as an opportunity to build a proof of concept for JSX in our codebase. JSX is a language with XML-like syntax, which makes ReactJS (ES6) code joyfully easy to read and write. Plus, it has the widespread support of a much larger community of developers.

It was relatively straightforward to rebuild the React components using JSX rather than Coffeescript (modules like decaffeinate can help speed up the process, though I found it easier just to rewrite them by hand). However, I hit a roadblock when it came time to compile the JSX and bundle it into the Javascript assets that were served onto the page. I was used to adding Babel to the Webpack config file and having it handle the compiling, bundling and delivering of a site’s assets. But there was no Webpack in our codebase. Instead, I needed to get Babel hooked into…the ASSET AGGREGATOR.

What is the Asset Aggregator?

“#AssetAggregator was written to help solve software-engineering issues that cropped up in a large (> 1500 view templates/partials) Rails application at scribd.com.” — code comments, 2010

The Asset Aggregator was born back in 2010, when Scribd was only 3 years old. At the time, Rails asset pipelines like Sprockets weren’t yet available and the developer community had not yet come up with a good solution for combining component-specific Javascript and Sass files into one larger file to be served on page load. In that situation, most companies manually maintained several large scripts and stylesheets, and designating which of these files to load per page.

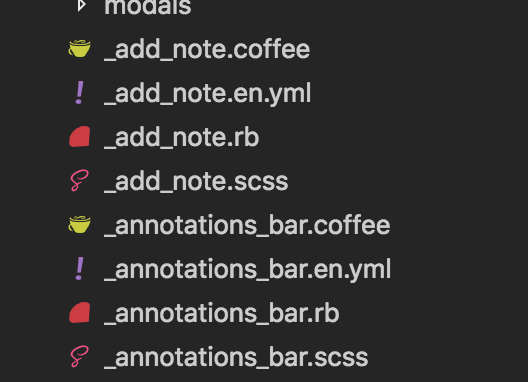

At Scribd, the app was growing fast, and in order to make their code scalable and reusable, our engineering team organized our web code into smaller, reusable Ruby partials, or “widgets” (Fortitude templates). Each partial was usually accompanied with a Coffeescript file and CSS file that shared the same name. When you added a widget to a larger template or widget, the alongside Javascript and CSS was also automatically included, attached and scoped to apply only to the adjacent Ruby code. Based on how you organized your widgets, there was an expectation that all the components in a shared directory would be readily available to other components in that same directory, and any external components could be explicitly included via a specification file in that directory.

Sample of our alongside file structure. If you added AnnotationsBar widget to your view, you would also get the Coffee and SCSS files along with it.

Sample of our alongside file structure. If you added AnnotationsBar widget to your view, you would also get the Coffee and SCSS files along with it.

It was a neat, organized system, and it meant that every page on the site would need to build out its own unique combination of Javascript and CSS, pulled in from the widgets that made up the page. How to make that happen, was another question. The world of Webpack and module imports would not appear on the scene for another several years. So our engineering team had no choice but to roll their own in-house asset aggregator.

The end result spanned over 50+ files and 13,000+ lines of code. When a deploy was kicked off, this Asset Aggregator would scan every file in every directory, starting with the specification file, and aggregate the stringified version of all the Javascript and CSS files that were needed into one large string. It took care of, among other things, ordering files, transpiling Coffeescript into ES5, automagically adding css class encapsulation to the Fortitude and CSS files to keep styling scoped to their classes, and making syntax errors traceable by wrapping individual Javascript classes in immediately invoked functions. It also took care of hot module reloading, which allowed developers to update the code on QA and local environments in realtime.

The Javascript and CSS files that were built out by the Asset Aggregator were then uploaded to our assets server. By calling append_asset with the name of the asset package you wanted in your Ruby widget, the appropriate script tag and stylesheet link would be appended to your HTML.

Javascripts and CSS were served up reliably, and all our widgets were neatly scoped and isolated thanks to the auto-magic of the Asset Aggregator. And all of it required minimal maintenance and manual intervention from individual devs.

I kind of imagine the Asset Aggregator as the Katamari Damacy video game my college roommate used to play…where you roll stuff up into a big ball everywhere you go.

I kind of imagine the Asset Aggregator as the Katamari Damacy video game my college roommate used to play…where you roll stuff up into a big ball everywhere you go.

Two years after Asset Aggregator was built, Webpack was released, but it made barely a ripple at Scribd. After all, our Asset Aggregator was customized to our codebase, all of our build and deploy tools were written around it, and it met the team’s basic needs for assets handling. Simply put, it worked. And if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The years passed, and Scribd hummed along. Outside of the company, the vast ecosystem of Javascript-focused libraries, plugins, and frameworks grew rapidly, and tools that vastly increased developer efficiency were released into the open-source community. Right around the time I started at Scribd, the company was expanding rapidly so several new hires were brought on soon afterwards. We all came in with the expectation that we’d be able to leverage the technologies we were used to using to solve modern front-end problems; technologies such as tree-shaking, de-duplication, compilers, and other Webpack enabled optimizations to manage the client-side code. But Asset Aggregator wasn’t built to easily accommodate new services.

It quickly became apparent that Asset Aggregator had outgrown its usefulness, and was now an obstacle standing in the way of progress. Simply removing it and replacing it with something else was not an option, given how intertwined it was with the structure of our views and assets. And besides, the languages and dependencies of our codebase were not so easily plugged into Webpack. This was going to be a long and arduous process.

Part 1: Asset Aggregator + JSX

July 2017

Let’s get back to where we left off, with the first JSX components written for Scribd’s Cancellation Flow. As mentioned, the challenge was integrating Babel with the Asset Aggregator in order to get JSX to properly compile to Javascript ES5 and get included in the final assets file that was deployed.

Firstly, we needed to add apackage.jsonfile and a .babelrc that would define which Babel packages we needed, and then run npm install during the Asset Aggregator build process. With Babel installed, the easiest way to get it working without adding Webpack was to run Babel’s CLI implementation.

{

"name": "scribd",

"version": "0.0.1",

"description": "JS dependencies for Scribd asset build",

"private": true,

"repository": {

"type": "git",

"url": "git@git.lo:scribd/scribd.git"

},

"dependencies": {

"[babel-cli](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-cli)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-cli)",

"[babel-plugin-transform-es2015-modules-amd](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-plugin-transform-es2015-modules-amd)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-plugin-transform-es2015-modules-amd)",

"[babel-preset-es2015](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-es2015)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-es2015)",

"[babel-preset-react](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-react)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-react)",

"[babel-preset-stage-1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-stage-1)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-stage-1)"

}

}

Using Open3, we could make a method that would take a JSX string, pass it through Babel, and return compiled Javascript.

def compile_es6(str)

output, status = Open3.capture2("#{Rails.root}/node_modules/.bin/babel -f transpiled.js", stdin_data: str)

output

end

Now, when Asset Aggregator came across a .jsx file as it scanned a directory, it would pass the string into compile_es6 and append the ES5 Javascript to the larger .js assets file that contained the other compiled Coffeescripts.

Part 2: Asset Aggregator + Webpack

October 2017

The use of Babel-CLI was a hacky stopgap to build out our proof of concept and show the team what JSX-React components could look like in our code. Once it was working, other engineers also began to write their features in JSX. The number of JSX components in our codebase grew, and we realized that we would need to incorporate Webpack into our build process, since it was a faster, more reliable compiler that followed industry standards. We addedwebpack into our package.json and called npm run buildas one of the first steps in the main deploy script.

Our package.json

{

...

"scripts": {

"build": "webpack",

"watch": "webpack --progress --watch"

},

"dependencies": {

"[babel-cli](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-cli)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-cli)",

"[babel-core](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-core)": "[^6.25.0](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-core)",

"[babel-loader](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-loader)": "[^7.1.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-loader)",

"[babel-plugin-transform-es2015-modules-amd](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-plugin-transform-es2015-modules-amd)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-plugin-transform-es2015-modules-amd)",

"[babel-preset-env](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-env)": "[^1.6.0](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-env)",

"[babel-preset-es2015](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-es2015)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-es2015)",

"[babel-preset-react](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-react)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-react)",

"[babel-preset-stage-1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-stage-1)": "[^6.24.1](https://npmjs.com/package/babel-preset-stage-1)",

"[glob](https://npmjs.com/package/glob)": "[^7.1.2](https://npmjs.com/package/glob)",

"[webpack](https://npmjs.com/package/webpack)": "[^3.5.2](https://npmjs.com/package/webpack)"

}

}

Our webpack.config:

const path = require('path')

const webpack = require('webpack')

const glob = require('glob')

module.exports = {

entry: getEntries('**/*.jsx'),

output: {

/*

Outputs .jsxjs files for easy asset aggregator integration.

See aggregated_javascript() in shared_assets.rb

*/

filename: '[name]js',

path: __dirname

},

resolveLoader: {

alias: {

'autogen': path.join(__dirname, 'webpack.auto_encapsulation.js')

}

},

module: {

rules: [

{

test: /\.jsx?$/,

exclude: /(node_modules|bower_components)/,

use: ['babel-loader', 'autogen']

}

]

}

}

function getEntries(pattern) {

const entries = {}

glob.sync(pattern).forEach((file) => {

entries[file.replace('src/', '')] = path.join(__dirname, file)

})

return entries

}

At build time, Webpack would scan through all the .jsx files in our code, and then generate a compiled JS file with the custom extension .jsxjs alongside the .jsx. After it finished, Asset Aggregator’s compiler would scan through all the directories, ignoring .jsx files but scooping up the newly compiled .jsxjs files, appending them to the larger assets files. These .jsxjs files were added to .gitignore so they didn’t clutter our repo with duplicate JS code.

This process worked adequately for our needs at the time. It allowed us to use Webpack to compile our JSX rather than the Open3-CLI hack, but it did slow down our build process by adding a step that involved installing, starting up and running Webpack, scanning through our entire codebase to build out .jsxjs files, and then scanning through the code a second time with the Asset Aggregator JS and CSS scanner.

Another hassle was, in order to get our auto-deploy script to pick up realtime changes in the code and auto-push them to our dev server, devs now had to run their two Terminal windows, one that ran a Webpack watcher, which would recompile .jsxjs files as the .jsx was changed, and another that ran the Asset Aggregator-powered auto-deploy script, which watched for updates to the .jsxjs files.

Part 3: Iterations and Optimizations

December 2017 to July 2018

The first “Asset Aggregator Retirement Plan” was drafted in December 2017. It called for the elimination of the Asset Aggregator system, which, in conjunction with Webpack, was creating large, unwieldy asset files that were potentially impacting performance (even including a 100 line file “button” file 10 times generated a lot of useless bytes).

The problem was that the one-to-one compilation and addition of JSX components to the larger assets files resulted in a high rate of code duplication, since Asset Aggregator was adding .jsxjs code for every dependency, without discriminating whether it was already included in that (or other) asset files.

We needed to disassociate our .jsx and .jsxjs files from the Asset Aggregator, to prevent the redundant includes. To do this, we would have to create packages for related .jsx files that other .jsx files could import from, and use Webpack to sort out what had been imported more than once and prevent duplicates.

Our first iteration of this was to create individual packages that matched the Asset Aggregator assets scheme, creating packages such as account_settings and book_preview and buttons, that would be included only once per page. Each package could then use Webpack to remove redundancy and de-dupe imports of components within that package.

We tested this out on a few pages, and the deduplication and reduction of assets sizes did indeed seem to be improving performance. However, it was soon noticed that, with the new package system, our auto-deploy was not working as expected. Some pages were including multiple packages (following our old pattern of allowing multiple assets files per page), which created multiple entry points that each had their own version of the included components. If a component was used in two different packages, updating that component’s file might cause our auto-deploy script to update one version in the files, but not the other.

Not being able to consistently auto-deploy significantly slowed down our developing process. To get a change up on a dev server, we had to redeploy the entire branch to the QA box, which could take anywhere from 8 to 15 minutes.

The correct solution would have been to reorganize our code so that each page only had a single entry point, rather than requiring the inclusion of multiple packages. However, we did not have the developer and QA resources to take on such an effort at the time.

The quicker fix was to create one large package (which we dubbed chrome.jsx) that included all of the JSX files in our code base, and include it once in our main assets file. This allowed us to reliably update the dev server with our Webpack watched changes, since every time we made a change, the entire chrome.jsxjs file would be updated. Auto-deploy worked again, and our workflow was back on track.

This fix came at the cost of page performance. We were now including our entire library of JSX components on every page, even though not every component was used. We had solved a duplication issue with Webpack, but created an unnecessary includes issue by trying to cobble together a hybrid solution.

Nevertheless, it was the best solution available to us at the time (after all, we did have to work on other things, like building actual features for our app), so we accepted it as a necessary evil and moved on.

Our web team is informally named Sonic (after the hedgehog). This is approximately what we looked like at this point, with our cobbled-together Asset-Aggregator+Webpack system and our unnecessarily large assets.

Our web team is informally named Sonic (after the hedgehog). This is approximately what we looked like at this point, with our cobbled-together Asset-Aggregator+Webpack system and our unnecessarily large assets.

Part 4: Removing Asset Aggregator completely: Proof of Concept

April 2018

The PDF reader page of the Scribd web application receives the highest traffic of all of our pages, and the need to speed it up for all users, including bots and users with slow connection, became a high priority in early 2018. The best way to do that was to generate a server-side rendered version of the React app that was our PDF reader. This immense effort is enough to be an entire blog post in itself, so I’ll give you the abbreviated version as it pertains to our Asset Aggregator.

Part of our team dedicated several months to rewriting our entire PDF reader in JSX, hooking it into Redux, and using Airbnb’s hypernova-react service to render everything server-side. This meant the build for doc page would be a completely different process, separate from how the rest of our site worked, and need to be fully Webpacked. It had its own webpack.config, its own node_modules, package.json, babel config…it was its own application, brought up to modern standards and using all the latest plugins.

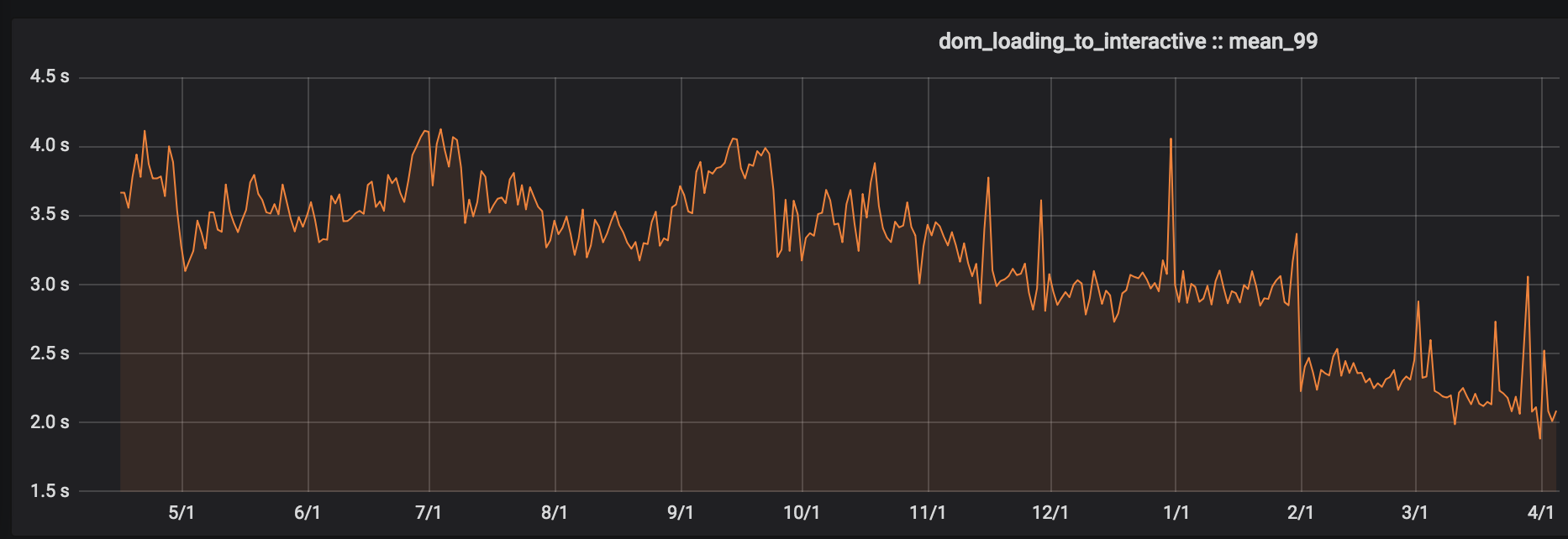

After it was finished, the performance gains were quickly apparent. The PDF reader was fast. Eliminating the third party dependencies and the unnecessary assets bundled by Asset Aggregator and leveraging services like Hypernova, we brought our PDF Reader load times down by two whole seconds!

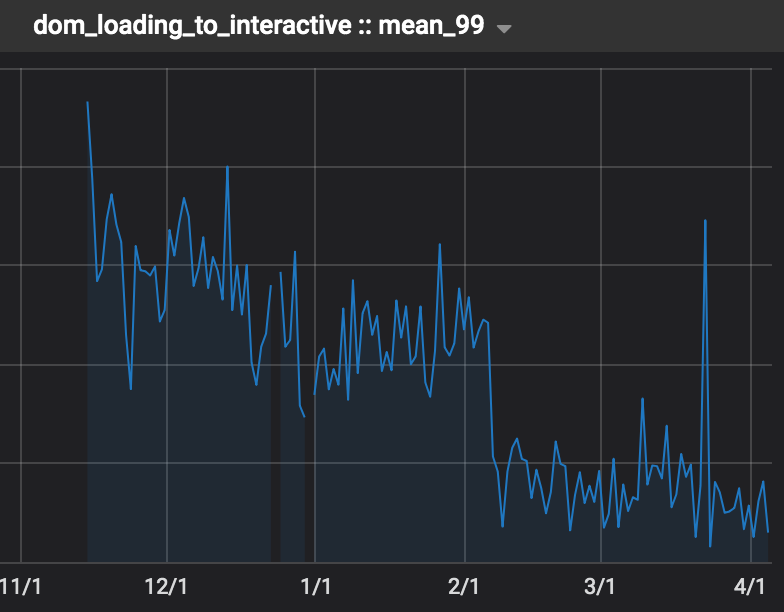

Logged out view time mean for PDF Reader. Full Webpack + Server-side rendering introduced in March for 50% of users, and turned to 100% by September.

Logged out view time mean for PDF Reader. Full Webpack + Server-side rendering introduced in March for 50% of users, and turned to 100% by September.

As the metrics from the PDF reader flowed in, the company saw the promise of where the rest of our site could be, if we could just disentangle our web application from the cruft of our legacy systems.

Part 5: Moving off Asset Aggregator

December 2018 to February 2019

In December 2018, a second Asset Aggregator removal plan was drafted. Having seen the wins made by our PDF reader, engineering leadership got behind the effort to remove Asset Aggregator once and for all.

The first step towards this was to go back to the original idea of creating individual packages for different parts of the site. This time, however, we would be careful about only have one entry point (package) per view, and depend on imports and requires to tell Webpack what other files were needed in this package.

In order to do this, we reconfigured Webpack to take in a specified list of entry points and compile and upload its bundled scripts, independently of Asset Aggregator. Then, to create a fully Webpacked package, we went through every page that was covered by each package, to make sure every script and style that was needed for all potentially rendered components were explicitly imported or required.

These packages files were then put in our /packages directory, with names like account_settings, books, audiobooks, static, etc. A sample package file now looked like this:

//packages/static.js

import "./globals.js"

import "./login.js"

import "./carousels.js"

// Importing individual JS files, especially main views and entry points

import "app/views/careers/index.jsx"

import "app/views/static/copyright/faq.coffee"

import "shared/react/tab_navigation.jsx"

//scss that is not imported through other JS, in this case these were all static ruby views

import "app/views/static/_help.scss"

import "app/views/static/about.scss"

import "app/views/static/about_container.scss"

import "app/views/static/accessibility_policy.scss"

import "app/views/static/contact.scss"

import "app/views/static/team.scss"

import "app/views/careers/department.scss"

In the webpack.config each package path was added to a converted_packages array, which was then added to the entry part of our module.exports.

let converted_packages = ["static", "home", "account_settings", "books", "audiobooks"]

module.exports = {

name: "development scribd",

mode: "development",

target: "web",

entry: {

babel_polyfill: "public/javascripts/babel-polyfill.js",

...converted_packages,

}...

Now, when a view called append_package, the compiled packages would be included on the page through link and script tags, loading public/javascripts/webpack/** files that were built by Webpack, rather than the old public/javascripts/aggregated/** files that were built by the Asset Aggregator.

In order to catch regressions early and prevent breaking changes, we incrementally merged the changes into our codebase. Three to four places in the site were converted at a time, and each branch went through a thorough QA pass, and code review. It was a huge job for our QA team, since it was the edgy use cases and user states that often depended on older code, which would break once the auto-magic of Asset Aggregator was no longer available.

One of the most common pitfalls was our legacy code’s dependence on previously available global function calls, which were no longer available globally and had to be imported. While tedious, this clean up helped us declutter our global namespace, and set the stage for better code hygiene and maintenance by only including scripts where they were needed.

This incremental package-ifying process was conducted by two devs, and two dedicated QA engineers across two months. Finally, in late February, all of the pages of site were fully managed by Webpack, with Asset Aggregator serving as a mere intermediary to run the build task.

We moved the Book Preview, Home, and Search Pages to Webpack at end of January. Note the drop in DOM loading time.

Book Preview Page, Logged Out

Book Preview Page, Logged Out

Search Page, Logged Out

Search Page, Logged Out

Book Reader, Logged Out

Book Reader, Logged Out

Part 6: Removing Asset Aggregator

March 2019

With all of our pages now fully packaged through Webpack, the time had come to fully remove Asset Aggregator from our codebase. The Ops team stepped in to get us across the finish line.

Previously, the Asset Aggregator built different content per environment by passing all code through ERB in order to access Rails URL helpers, which would write full, absolute URLs (including hostnames) everywhere helpers were used. In order to generate environment-specific content, Asset Aggregator build had to be run on deploy. The production build was later moved to CI, which meant that Webpack had to be run in both CI and deploy stages to accommodate for testing and production environments.

After the transition to Webpack, we could use relative paths instead of absolute, which meant that the build step could be moved completely over to the CI pipeline. Ops added a step in Docker where Webpack would build and upload the bundled assets to Artifactory. Then, at deploy time, the assets were simply downloaded and unpacked from Artifactory and made available to our web application.

This reordering of steps added 3 minutes to our CI time, but cut down our deploy-to-production from 55* to 10 minutes! We deployed twice a day, and this time savings meant our engineering and QA team had 84 minutes of their work day back!

The final touch was the glorious MR that deleted the 13,600 lines of Asset Aggregator code.

- It should be noted, some of the slowness in** **our former deploy pipeline was due to the fact that we were using two different systems (Asset Aggregator + Webpack), but after the former was removed, the gains of switching to a modern, optimized module bundler were undeniable.

Part 7: Fully Webpacked

Now that we were were fully off of the clunky, slow software that was Asset Aggregator, we could take advantage of all the new modern plugins with one or two lines in our webpack.configor package.json. We could leverage tree-shaking and de-duplication tools to slim down our asset packages even further. Updates and versioning would be easier. And it brought our codebase up to modern industry standards, which mean there was documentation to support the tools we were using, and it was much easier to onboard new developers and have them hit the ground running.

We could also now improve our code test coverage for React components. Our old setup and dependence on various globals made it near impossible to get our components isolated, so we were only able to implement basic Javascript tests with Jasmine specs. With these global dependencies removed, we could leverage fancy new tools like Jest, Enzyme and Snapshot testing!

This was the Sonic team after being fully Webpacked!

This was the Sonic team after being fully Webpacked!

Lessons Going Forward:

We learned a lot through the last two years, not only in terms of how to cobble together solutions to make new systems work with old, but also how to handle large technology transitions both as a team and a company as a whole.

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/search/photos/forest-freedom?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/5864/1*1fTRsy732whdmdPMlxfH8A.jpeg) Photo by Pranam Gurung on Unsplash

Photo by Pranam Gurung on Unsplash

-

*Make code updates a regular thing, smaller changes are easier than a huge overhaul. *For a long time, one of the main obstacles in the way of removing Asset Aggregator was the feeling that much of our older code and their dependencies were not compatible with Webpack. Had we kept our code relatively updated throughout the years and removed libraries and files that were no longer being used, I believe the path forward for Asset Aggregator clean up would have been more clear. For example, Asset Aggregator was built before Rails asset pipelines were available. Once we moved to Rails 3, we should have also transitioned our custom Asset Aggregator to the Rails asset pipeline. By failing to do so, we bought ourselves years of pain and further entrenched our code in an outdated solution. In the process of transitioning out of Asset Aggregator, we found many areas where code was either extremely outdated and could be rewritten, or even large segments of dead code. In one place, we rewrote a few lines of code and deleted the YUI library, which resulted in 187,891 line deletions! Aside from that, keeping a codebase relatively up to date enables a team to take advantage of open-source tools that help manage transitions (which usually can only go back a few versions), and psychologically prevents a feeling of “stuckness” and “sunk costs” which can discourage updates even when the status quo is slowing a team down.

-

Know when to change. Keeping a codebase up to date is easier said than done for a large company whose growth and performance metrics don’t often consider tech debt. And often, it’s easy to get into the mindset of “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it”. Asset Aggregator served the Scribd team well for almost a decade. However, as the team grew and the developer eco-system also evolved, we hit a point when the Asset Aggregator became a hinderance to our growth. It’s important for every team to be able to identify the moment when it takes more time and energy to maintain and build workarounds for an older tool, compared to the time and energy it would take to retire it and transition to modern solutions. Both processes are expensive. But at a certain point, if the legacy code becomes too difficult to maintain and use, it’s better to bite the bullet and devote the resources to overhaul the system.

-

Avoid auto-magic. One of Asset Aggregator’s lures and ultimately, traps, was the amount of auto-magic it took care of in the aggregation process, that made it easy for the developer to build out code without being fully aware of what was happening under the hood. Things like auto-encapsulation and immediately invoked function wrappers were taken for granted. The fear of undoing auto-magic that we didn’t fully understand contributed to the feeling of inextricability and being “too tied in” to the Asset Aggregator. A little extra work on a developers part in making things explicit (for example, manually writing enclosing classes rather than having them added at build step) makes it much easier to update your stack in the long-term.

-

Incremental transitions help make the process smooth and minimize regressions. Our transition from Asset Aggregator to being fully Webpacked was a slow and gradual one, and started with a proof of concept built out by one developer. After that was demo’ed, team members had the choice to either write in JSX/ES6 or continue with Coffeescript. This made for less transitional friction in the beginning, and ensured that the introduction of a new language wasn’t jarring or disruptive to other engineers. As time went on, more and more of the site was converted to JSX until a codebase that was fully Webpack-able could be easily envisioned. In the last two months of the Asset Aggregator removal process, we kept our MR’s reasonably small, allowing QA and other developers to thoroughly review the changes. This prevented breakages in production, made it easier to identify where and why things broke, and informed subsequent page updates, making the transition as seamless and painless as possible.

-

Sometimes you have to go big and slow in order to go small and fast. During the initial stages of introducing Webpack to our build process, we were running two file bundling systems in sequence for every deploy. Running Asset Aggregator once and then running Webpack on every app host added time to our deploys for the two years we were using the hybrid system. And in the auto-deploy workaround described in Part 3, we increased the size of our JS and CSS files for every page, loading unnecessary bytes onto each page in order to allow our engineering team to continue building out JSX components. Luckily, once the entire site was transitioned and we could be fully Webpacked, we saw deploy time decrease to speeds never seen in the history of the company and the size of those assets shrunk by more than half!

-

Make sure testing environment is as close as possible to production environment and all devs are aware of the changes and potential impacts of transitional changes. Early on in the Webpack transition, a dev merged a component that had no Asset Aggregator tie-ins and was fully JSX. Our production asset pipeline didn’t properly build out the assets, and it broke the Download Document UI for our users (a crucial part of our application). This was not caught during QA because our testing environments were set up to load assets differently than production. This wasn’t a Webpack issue, but rather an issue with how we had our hybrid build system set up, and its discrepancies between development and production environments, which were never fully communicated between teams. The long-term lesson there was to create as much parity as possible between testing and production environments, and make sure other developers are aware of the transition and can do additional testing around their features to make sure things are working as expected.

-

Good communication, understanding, and buy-in from other teams is critical. While Webpack is predominately front-end concern, it was invaluable to have discussions with Ops, Pproduct, and QA about the benefits of moving to Webpack and retiring Asset Aggregator. Understanding how the new system worked and potential pitfalls enabled QA to know to look out for missing CSS and interactive functionality when they were doing their regression passes. And Ops involvement was integral in every step of the transition over the two years, from introducing Babel and Webpack to our build steps, to finally removing the Asset Aggregator.

Conclusion

Getting fully onto Webpack has been a major unblocker for the Scribd web team, and has greatly increased the speed at which we are able to make page performance improvements and incorporate newer modules and plug-ins. Within a month, we have added Babel-loader caching, splitChunks optimizations, and contentHashes to cut our asset sizes even further, and incorporated React-Loadable and Snapshot testing into our codebase.

What’s more, with our codebase cleaned up and this experience behind us, there is a clear path forward for our team for continuously improving and maintaining our codebase. In the last two years, the Scribd application has gone through a Rails 3 to 4 transition, a React 14 to React 16 migration, a jQuery 1 to jQuery 3 migration, and this large Asset Aggregator to Webpack transition. We are well-versed in how to implement transitions that are smooth and non-disruptive to the rest of engineering, and can introduce newer technologies with more confidence, making for a more secure, faster application for our end-users.

The Asset Aggregator served us well for almost a decade, and was no small feat by the Scribd engineering team in a time when such tools did not yet exist in the wider developer community. However, with spring cleaning ahead of us and the Marie Kondo phenomenon sweeping the country, it’s the perfect time to assess our code clutter. Alas, the Asset Aggregator has ceased to spark joy at Scribd. So the time has come to thank it for its service, and let it go.

Or, in the words of another teammate, “See ya later, Aggregator!”

Acknowledgements

This monumental effort would not have been possible without the contributions everyone on the Web (Sonic) team who helped in converting and updating components, and most notably: Jesse Bond, who wrote most of the custom Webpack configurations and hybrid systems and Luke Stebner, who outlined the first Asset Aggregator retirement plan for the team.

Thank you to Stephen Veiss, Scribd’s Ops lead who helped update, tweak, and integrate all of our “proposals” into the larger build and deploy processes for every stage of this transition.

And of course, big thanks to our tireless QA team for making sure nothing crashed as we changed the wheels on this moving vehicle.

If you want to work on changing how the world reads, come join us! www.scribd.com/careers