The final signficiant feature to look at are Data Factories, which I’ll explain shortly, and after that I’ll run through a grab bag of additional features that I haven’t covered yet (because I just wasn’t good enough at anecdotally dropping them into previous examples).

Data Factory: What is it and why are you trying to make things more complex?

This is a feature that I didn’t anticipate when I started this project, but one that became a necessary addition after dogfooding LiveCollections in Scribd.

What made it necessary is that the calcualtions in CollectionData are based on generic types that adopt UniquelyIdentifiable and as a result, define equality comparisons using the default object equality function. This is problematic as we are bound to a single definition of equality per data type.

While that’s normal for data management, it’s not ideal for a view representation of that data. Equality is what intrinsically defines a reload **of a row/item in the view. This inequality informs us that a change has taken place. The problem is that **we may not want to use the same concept of equality in two different presentations of our data. Specifically, we may want to factor in additional pieces of information that modify our data, but are extended metadata rather than root properties.

There are two solutions to this problem:

-

Simply create a wrapping class/struct to define the tuple of data type and additional metadata.

-

Create that same wrapping class/struct but support it with an object that adopts the protocol UniquelyIdentifiableDataFactory and will build the wrapper for you.

Solution 1 is completely fine for the limited case, whereas solution 2 hides away the mapping logic to transform the data, and allows you to expose a standardized update method (which you may want for custom protocol conformance, injection, and testability).

If the wrapper class is MovieWrapper for the standard type Movie, then here’s what the update function looks like for Scenario 1:

func update(_ data: [MovieWrapper], completion: (() -> Void)?)

For solution 2:

func update(_ data: [Movie], completion: (() -> Void)?)

A small, yet significant shift in usage and abstraction as it now matches the same API we’ve been using for all of our examples up to this point.

Ok, how do we build a data factory?

We’ll answer this in the final scenario…

Scenario 9: Using a Data Factory

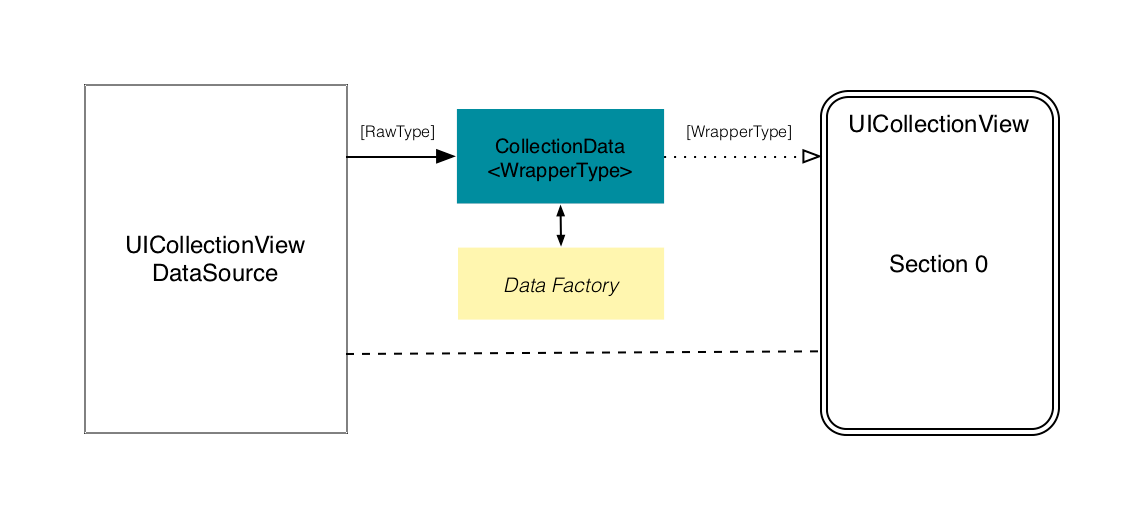

Fg. 11: The CollectionData object holds the reference to your data factory

Fg. 11: The CollectionData object holds the reference to your data factory

Lets start with a short and simple situation. The data object will be Movie and the metadata we want to add is the booleanisInTheaters: Bool. Essentially, even if all of the data on the movie struct stays exactly the same, but the movie ends its theatrical run, we want to reload the cell in our view (presumably to remove a banner or badge).

For this, we’ll need a new struct that will be used in CollectionData. We can call it DistributedMove to indicate a movie that’s been picked up to be shown in theaters. It looks like so:

struct DistributedMovie: Hashable {

let movie: Movie

let isInTheaters: Bool

}

extension DistributedMovie: UniquelyIdentifiable {

var rawData: Movie { return movie }

var uniqueID: UInt { return movie.uniqueID }

}

This is a very simplified model, but it suits our needs.

In this example, we’ll also have some controller that can provide us the information to determine if a movie is currently in theaters or not. Lets call this objectInTheatersController, and it will expose the singular function func isMovieInTheaters(_ movie: Movie) -> Bool.

Ok, we now have all of the tools we need to build our factory. This new factory class will need to adopt the protocol UniquelyIdentifiableDataFactory:

public protocol UniquelyIdentifiableDataFactory {

associatedtype RawType

associatedtype UniquelyIdentifiableType: UniquelyIdentifiable

var buildQueue: DispatchQueue? { get }

func buildUniquelyIdentifiableDatum(_ rawType: RawType) ->

UniquelyIdentifiableType

}

The RawType value (which you’ll remember previously was always the same as Self) now becomes Movie. That is what determines which type the update method takes in CollectionData.

Note: buildQueue defaults to nil by default via extension, and only needs to be used if your data needs to be built on a specific queue.

This protocol isn’t as scary as it looks when used in practice:

struct DistributedMovieFactory: UniquelyIdentifiableDataFactory {

private let inTheatersController: InTheatersController

init(inTheatersController: InTheatersController) {

inTheatersController = inTheatersController

}

func buildUniquelyIdentifiableDatum(_ movie: Movie) -> DistributedMovie {

let inTheaters = inTheatersState.isMovieInTheaters(movie)

return DistributedMovie(movie: movie, isInTheaters: inTheaters)

}

}

This is really just an object that holds onto your state lookup controllers and applies them to your data to build the new object.

How do we use it?

From here, the only code that really changes is your initializer:

let dataFactory = DistributedMovieFactory(inTheatersController: inTheatersController)

collectionData = CollectionData<DistributedMovie>(dataFactory: dataFactory)

Now, anytime you call collectionData.update(movies), under the hood it uses the data factory to build a new array of DistributedMovie objects and uses those for equality.

Also take note that while you update with [Movie], the subscript function returns DistributedMovie, which you’ll need to properly decorate your cells.

With just these few tools, we can now build any flexible custom class/struct to give us customizable and contextual animations for any view we need!

Scenario 10: Non-Unique Data in a Single Section

The initial implementation relied solely on all data having completely unique identifiers, but I realize that is a limiting factor that is unnecessary. At the end of the day, all data *does *need to be uniquely represented, but surely this can be handled under the hood automatically, right? Right.

The solution was to leverage data factories to silently create a unique representation of your data object to manage the delta calculations.

The factory is created for you in the initializer so all you have to manage is setting up your data class by adopting the (predictably named) protocol NonUniquelyIdentifiable, defined as:

public protocol NonUniquelyIdentifiable: Equatable {

associatedtype NonUniqueIDType: Hashable

var nonUniqueID: NonUniqueIDType { get }

}

And then instead of using CollectionData, instead you’ll use the typealias:

typealias

NonUniqueCollectionData<NonUniqueDataType: NonUniquelyIdentifiable> = CollectionData<NonUniqueDatum<NonUniqueDataType>>

To set up your data like so:

let collectionData = NonUniqueCollectionData<YourClass>()

As you can see, it wraps your data type in a container NonUniqueDatum. It then converts your data to the container type and adds an occurrence: Int value to help make it unique.

As a result, when you fetch your data via subscript or items*, *you will need to unwrap it with the rawData accessor.

let movie = collectionData[indexPath.item].rawData > Note: The matching algorithm is quite basic, if your array is **[A, B, A, C, D, B] **then it gets mapped to **[A(1), B(1), A(2), C, D, B(2)] **and animations are performed accordingly.

Scenario 11: Non-Unique Data in Multiple Sections

Exactly as described above, except you’ll use the typealiased collection type:

typealias

NonUniqueCollectionSectionData

<NonUniqueSection: UniquelyIdentifiableSection> = CollectionSectionData<NonUniqueSectionDatum<NonUniqueSection>>

where NonUniqueSection.DataType: NonUniquelyIdentifiable

And set up your data:

let collectionData = NonUniqueCollectionSectionData<YourSection>(_)

Similarly, your data is wrapped in a container object NonUniqueSectionDatum where your items are also wrapped as NonUniqueDatum. So you simply access your data like so:

let movie = collectionData[indexPath].rawData

Scenario 12: Not Setting a View Object on CollectionData

In all of the scenarios so far, we’ve always set a view onto the CollectionData object and let it manage the animations directly for us. What if we don’t do that?

There is an additional scenario at the end, Scenario 10, which covers this use case. Basically, you are just decoupling the calculation of the delta with the performing of the animation.

The code looks like this:

let delta = collectionData.calculateDelta(data)

let updateData = {

self.collectionData.update(data)

}

collectionView.performAnimations(section: collectionData.section,

delta: delta,

updateData: updateData,)

Or if you decided you wanted to skip this animation altogether:

collectionData.update(data)

collectionView.reloadData()

This is here for some added flexibility in the event that you don’t want animations on every update, you want to more tightly manage the timing of animations, or perhaps you juse want the delta and have no view at all.

Due to the added complexity of delta timing, I haven’t added an equivalent feature onto CollectionSectionData, and to use that object you must still assign a view to it.

The Grab Bag

Ok, lets wrap this up before we accidentally end up in Part 6… that’s too many parts.

There are a few remaining features that didn’t really get touched upon but can be explained in isolation, let’s run through them all here.

public var dataCountAnimationThreshold: Int

CollectionData has a settable variable dataCountAnimationThreshold that defaults to the value 10,000.

What this does is short circuits any complex delta animations and replaces them with a reloadSection animation. I mentally think of this as smearing around a deck of cards rather than shuffling them cleanly. The animations aren’t precise, they just make it look like stuff is moving around and then shows the final data set. It’s somewhere between reloadData and performAnimations.

If you remember back to the performance chart in Part 1, we identified 10,000 rows as the practical performance dropoff point which is why it is our default value here. You can raise or lower this number as you see fit.

Additional CollectionDataManualReloadDelegate functions

Actually, one additional function:

func preferredRowAnimationStyle(for rowDelta: IndexDelta) -> AnimationStyle

Where AnimationStyle is:

public enum AnimationStyle {

case reloadData // no animation

case reloadSections // animated but not precise

case preciseAnimations // animated and precise

}

Aside from dataCountAnimationThreshold above, this gives you granular control to determine how you want to animate any specific delta. There may be conditions that result in an animation you don’t want to perform, and this is where you can either “downgrade” it to reloadSections or abort it completely with reloadData.

In most cases just return .preciseAnimations.

The delegate CollectionSectionDataManualReloadDelegate

I didn’t specifically call this out earlier, but this is the delegate protocol you must adopt when using CollectionSectionData. It inherits from CollectionDataManualReloadDelegate and adds a single method:

func preferredSectionAnimationStyle(for sectionDelta: IndexDelta) -> AnimationStyle

Like the row animation function above, this allows you to make a determination on the section animations.

For a little clarity, section animations always come before the row animations, (i.e. a section that moves will animate to its new position before any items are inserted, deleted, moved in/out, or reloaded from that section).

The delegate CollectionDataDeletionNotificationDelegate

You can adopt this protocol and set it on either CollectionData or CollectionSectionData.

It has a single function:

public protocol CollectionDataDeletionNotificationDelegate: AnyObject {

associatedtype DataType: UniquelyIdentifiable

func didDeleteItems(_ items: [DataType])

}

Because it requires an associatedtype, setting the delegate requires you to call:

collecionData.setDeletionNotificationDelegate(self)

By adopting this, you will get a list of items that were deleted in the previous update. This is a hook for you in case you want to add logging, send off analytics, clear up memory for related objects, or to simply debug some code.

Appending Data

I didn’t cover this in the main examples because it’s such a trivial use case. If you are creating a table or collection view to be a paginated service where all updates are always appends, you can simplify your calculation time and just call:

collectionData.append(data)

Because the delta is literally just a range of integers, appending ignores the dataCountAnimationThreshold and always attempts to animate.

Appending is also supported inCollectionSectionData, but in this case it only supports appending whole sections. I.e. you can’t append row data to a section already displayed. You would have to call update to get that behavior.

See What’s Currently Calculating

With CollectionData, using the accessors subscript or items will let you see the current data set, but as processing happens on background queues, there will be a period of time where we are processing an updated data set while the previous data will still be returned from the above accessors.

To see if you’re in this state, there are two additional accessors, isCalculating and calculatingItems which will give you read access to the data currently being processed. This is information you may choose to simply ignore, but it can be helpful for some logical decisions based on your workflow.

Similarly, with CollectionSectionData there are the equivalent methods isCalculating and calculatingSections.

The End

We’re done!

Thanks to all of the dedicated readers who made it to the end, I genuinely hope you find **LiveCollections **to be a tool that both adds a visual flair to your app, and reduces the stress of using collection based animations full-stop.

If you have any suggestions or feedback about new features or code tweaks you’d like to see, I would love to hear from you. Feel free to submit issues on GitHub or email me directly at stephane@scribd.com.

I’d also like to thank my fellow developers at Scribd, both past and present, Ibrahim Sha’ath, Paris Pinkney, and Théophane Rupin for their contributions, either in bug fixing, code reviews, or design feedback.

Revisit

Part 1: Get Animated with LiveCollections for iOS

If you want to work on changing how the world reads, come join us! www.scribd.com/careers

Resources

Download from Scribd’s GitHub repo