Whether it’s for education, business, or fun, access to books is crucial for everyone, regardless of their abilities. Contrary to popular belief, access to books is a broader issue that far surpasses the domain of visual impairments. Everyone benefits from a good book.

Roughly 10% of people in the developed world, and 15% in the developing world have some degree of print impairment. These are people with visual impairments, with dyslexia, or with motor disabilities which can seriously affect their ability to read ¹.

At Scribd, our goal is to bring together the best books, audiobooks, and articles to help readers become their best selves. We are a subscription service that allows its members to read unlimited electronic books and audiobooks for a monthly fee. At its heart is the HTML based e-book reader component, which went through a major overhaul in 2017. When designing the reader, we wanted its accessibility to be a product of good design and coding practices — not just a half-baked add-on.

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com?utm_source=medium&utm_medium=referral)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/10944/0*tgrbqcp5gRTa3RFH)

Creating an eBook reader for the Web is complicated. Making it universally accessible is an even greater challenge. In order to understand the complexity of the challenge, let’s take a look at some of the permanent, temporary, and situational disabilities that affect how people interact with eBooks.

-

Visual: Blind & Low Vision → Color Blindness → Blurry Vision After Laser Surgery → Reading in Bright Sunlight

-

Aural: Deaf → Hard-of-Hearing → Ear Infection → In a Large Crowd

-

Motor: Quadriplegic → Parkinson’s → Broken Arm → New Parent

-

Cognitive: Dementia → Dyslexia → Seasonal Allergies → Multitasking

By designing for someone with a permanent disability, someone with a situational limitation can also benefit. For example, a device designed for a person who has one arm could be used just as effectively by a person with a temporary wrist injury or a new parent holding an infant ³.

Although, there are still design and coding issues that we will improve to be even better, we stand proud of what we have achieved. This article is the result of a mountain of trial and error, user studies and feedback. You’ll find design patterns and code snippets that worked well for us. But, you’ll also find things that we thought were great features, but didn’t end up working so well in the real world.

Employing Great Color Contrast

Color contrast is one of the most important aspects of Web accessibility. A ton of research and best practices on the subject are already out there. Our designers made sure that text and controls have at least 4.5:1 contrast ratio with their immediate background in all three themes. This allows people with moderately low vision to read text and distinguish controls without any additional help. It also helps someone read a book under bright sunlight outside.

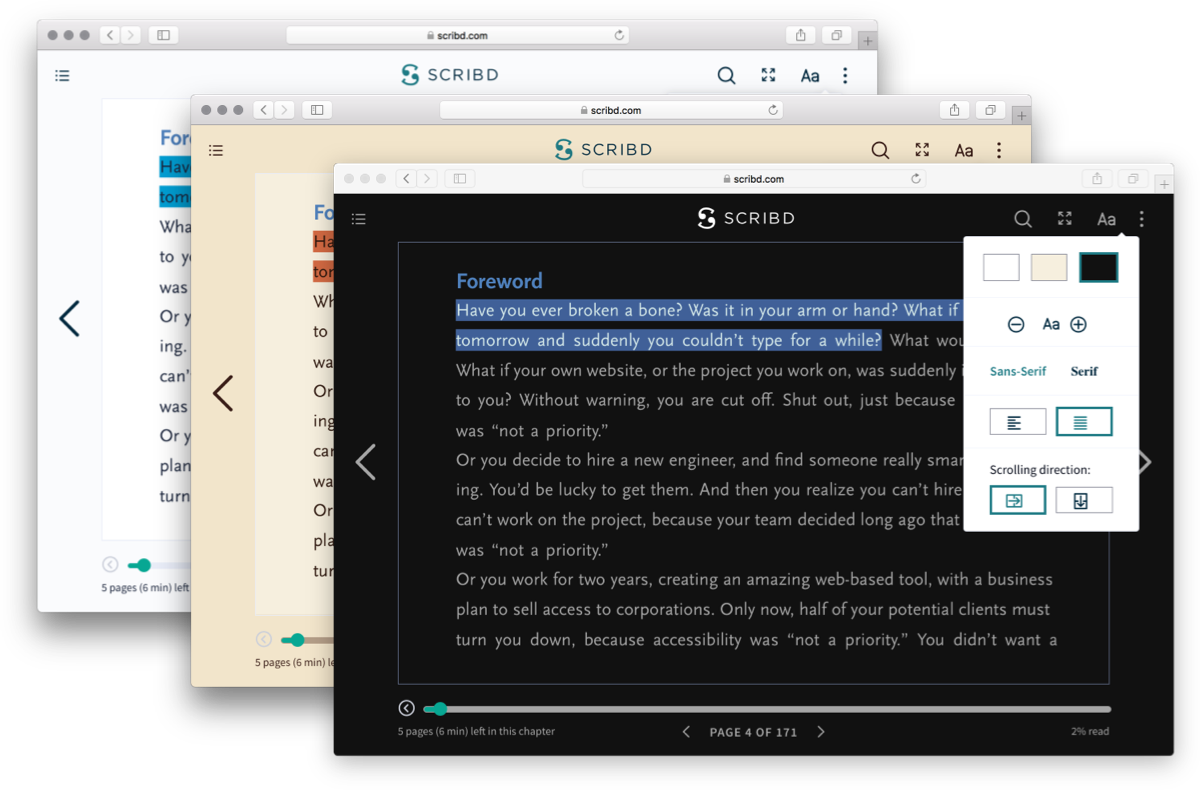

Scribd’s eBook Reader UI in Different Color Themes

Scribd’s eBook Reader UI in Different Color Themes

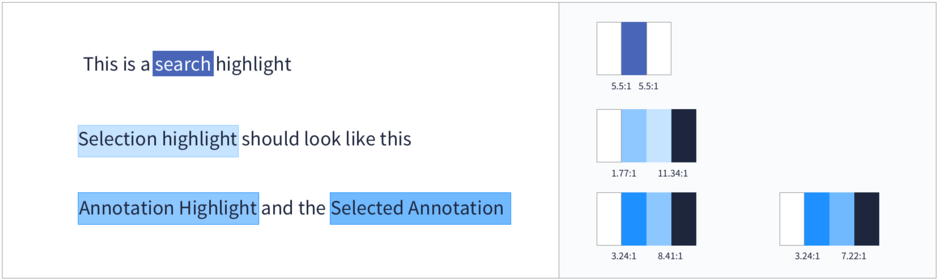

However, there’s one aspect of contrast that’s often overlooked — text selection and highlighting. We made sure that search results, selection and annotation highlights have adequate color contrast. Our goal was to keep a 3:1 contrast ratio between selection color and background, and 4.5:1 between text and selection.

All of this may sound simple. But, given the relatively narrow color palette available to achieve high contrast text and graphics, color contrast was a project in itself for our designers.

Different Text Highlight Colors and Their Contrast Ratios

Different Text Highlight Colors and Their Contrast Ratios

Remaining Usable in High Contrast Mode

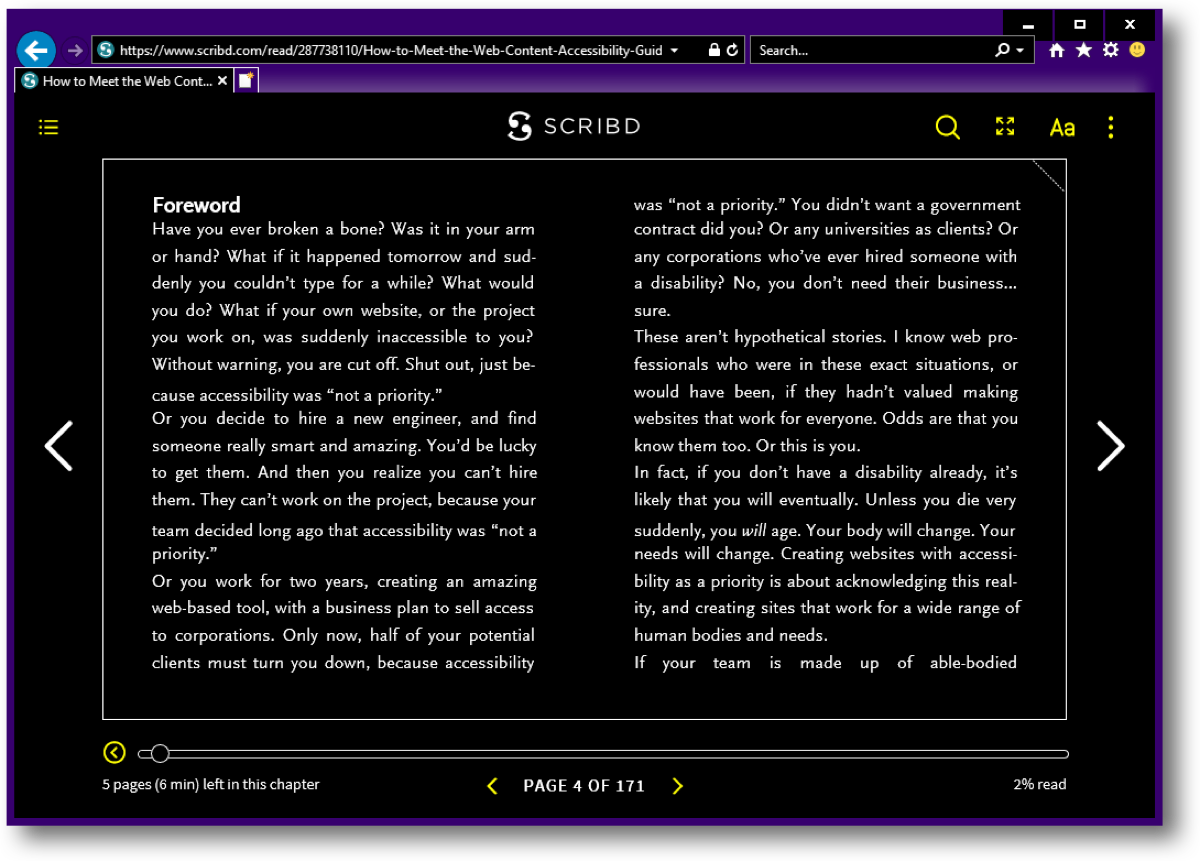

Windows has a High Contrast Mode which disables all background colors and custom styling, and replaces them with contrasting colors when activated. This is unlike other Operating Systems that just invert the screen colors.

We made sure that Scribd’s reader works well in Windows High Contrast mode by adjusting our CSS styles and making High Contrast mode testing a part of our QA process.

Scribd’s eBook Reader in Windows High Contrast Mode

Scribd’s eBook Reader in Windows High Contrast Mode

A good example is the scrubber bar at the bottom of the reader. The scrubber track doesn’t have a visible border in default browser view. So, it was invisible in High Contrast mode since it relied on background color.

A transparent border around the scrubber works best to solve this problem. This way, we can maintain the original design, but still have a visible border when High Contrast is activated.

If that’s not an option, you can always use a High Contrast specific CSS rule for adding a border when High Contrast is activated. But, the major caveat is that it only works with Internet Explorer.

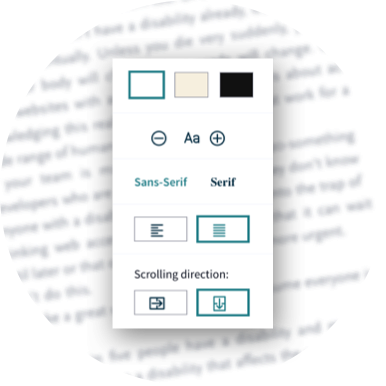

Providing Alternative Display Options

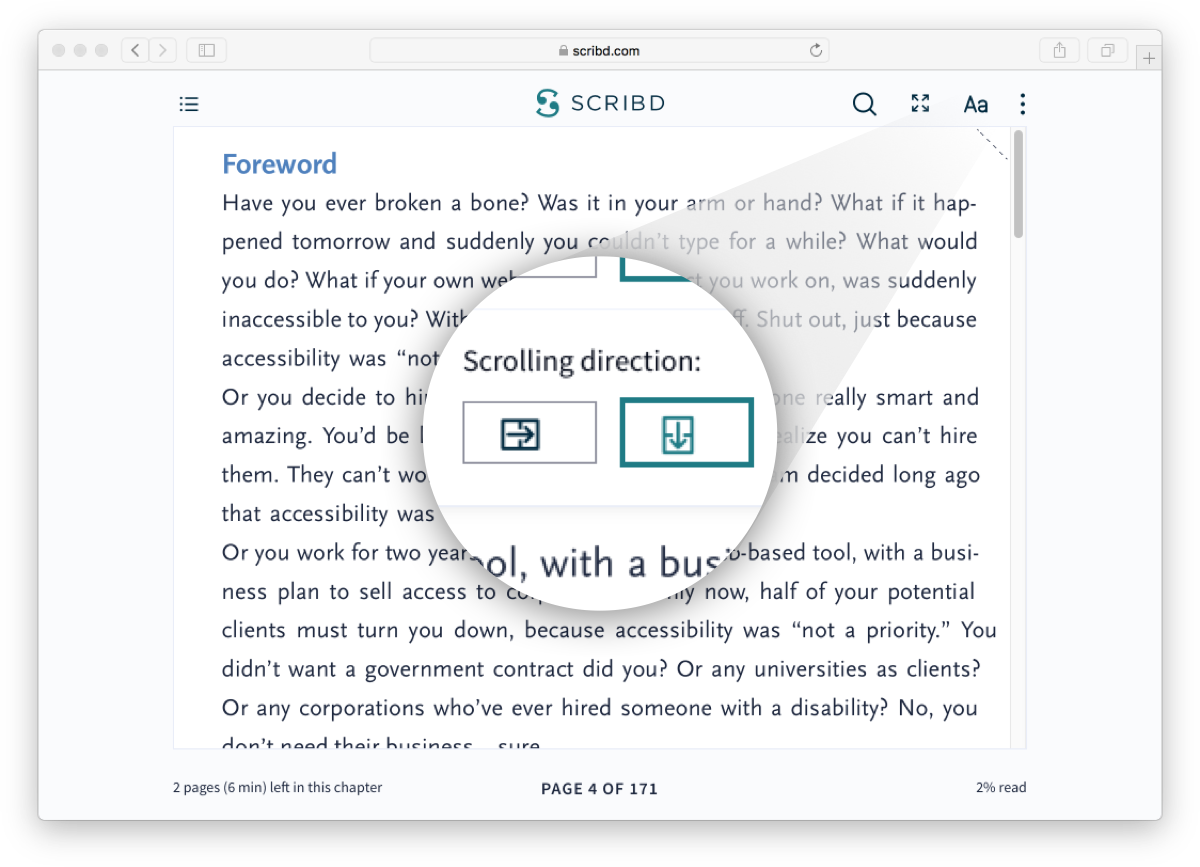

Scribd’s reader has two layout options; vertical and horizontal. The horizontal mode acts very much like a conventional book, where content is presented page-by-page. The vertical mode works a little differently. It displays the entire chapter at once, and allows you to scroll vertically.

During user research, we found out that screen reader users liked the Vertical Layout better, because it meant fewer page turns, and, the entire chapter can be read at once.

In addition to scroll direction, we also provide users the opportunity to switch between Serif and Non-Serif fonts, as well as adjusting text alignment.

People with cognitive disabilities often have trouble with blocks of text that are justified. The spaces between words create “rivers of white” running down the page, which can make the text difficult to read ².

Although it varies from person to person, a person with Dyslexia is likely to find it much easier to read the content when it’s left justified and in a sans-serif font.

Bookmarking Should Be Intuitive

Bookmarks are one of the most used features on an eBook reader. In our reader, there are a couple ways to add and manage bookmarks. You can simply click on the dog-ear on the top right part of the page, or use the actions menu to add a bookmark. It’s also possible to list all the notes and bookmarks in a modal window.

We thought that providing multiple methods to add and manage bookmarks would provide a better experience for assistive technology users. However, it turned out to be one of the tasks that had a lower satisfaction rate in our usability tests.

Although all participants were able to complete the task, 40% of them rated the task as “difficult”, and said “it took more time than expected” to complete. It turns out, despite the fact that it mimics a real-world concept, that the “dog ear” wasn’t in fact that intuitive, and users had difficulty finding its alternate in a dropdown menu. It would probably be more useful if the bookmarking feature is always present in the UI as a button with a visible label, instead of being reachable in a dropdown menu.

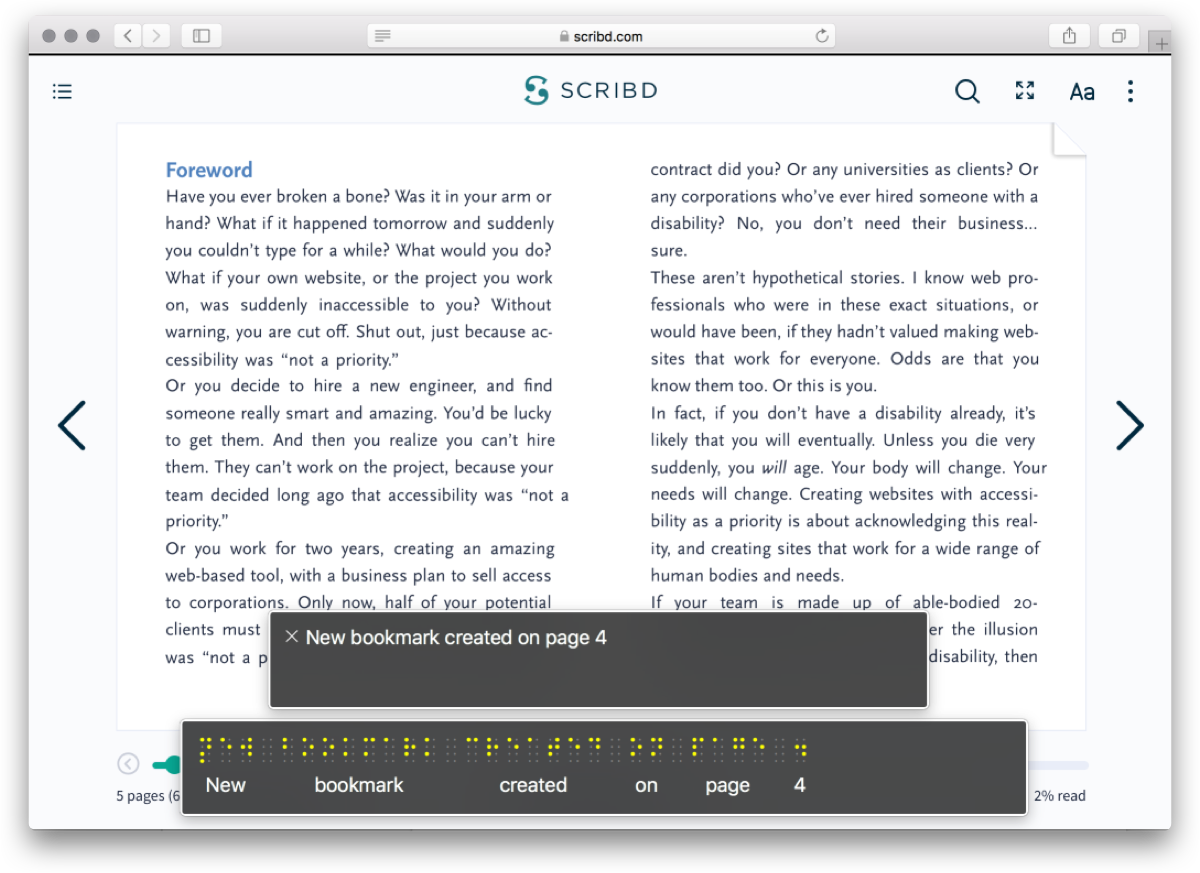

In order to provide a better screen reader experience, we used a live region to notify users when a bookmark is added or removed. We also made sure the bookmark indicator remains visible at all times, and, that its different states are distinguishable in High Contrast mode.

Heading and Landmark Structure That Make Sense

Headings are a major navigation strategy for assistive technology users. They serve as labels for major sections of a web page or an app. An e-book reader is an interesting case in terms of how headings are used. Because the major user interface groups of the app need headings, but there’s also the actual book content that already has headings in it.

Our heading structure conveys the current book title, current chapter and the headings in content in a nested structure. The title of the book is an H1, chapter is H2 and they are always present on the page. We opted to have them as “visually hidden” elements, so that they are only available for assistive technology users. However it’s always better to keep these elements visible at all times if your design allows for it. The rest of the headings in document content are nested as H3 and lower.

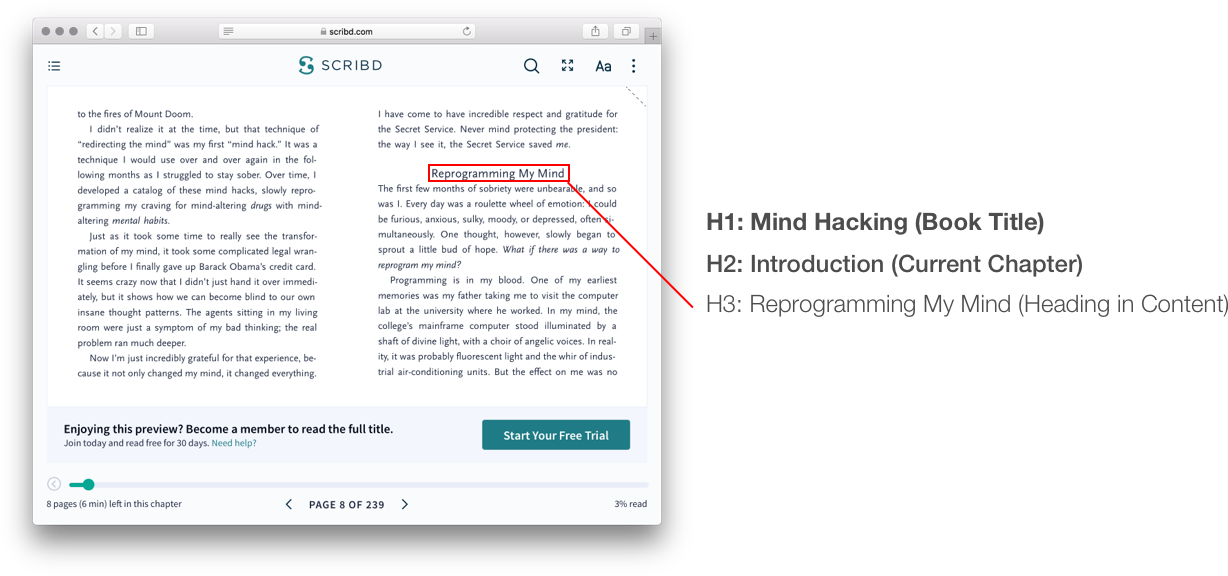

Mind The Screen Reader Experience

In addition to the desktop, our e-book viewer is used on the mobile web, as well as being embedded in our native mobile apps. This meant that making the reader work with a variety of screen readers was a challenge. The variety of content, and the complex algorithms used for rendering text and visuals on the page, made it a challenge to make it accessible to screen reader users. In order to provide a great user experience for assistive technology users, we decided to generate a cleaner HTML version of the content, and provide it in tandem with the visible content.

Ideally, the text read by assistive technologies should be the same one that’s available to visual users. However, this is challenging in complex page layouts. When this is the case, it is important to make the text, if not the graphics available to assistive technology users.

The simplified HTML content is placed inside a <main> element so that it can be easily located when necessary. The content inside the simplified HTML version only has paragraphs, links, image descriptions and headings. It’s also a live region. When a page flip happens, the content begins to read automatically. So, the screen reader users don’t have to find the previous/next links every time they finish a page.

Current page and reading progress are also announced at every page turn. The information is placed inside a container with the role of ‘status’, so that it can be read with a key combination on most screen readers.

The Keyboard Focus Quirk

One tricky — and probably the most awkward quirk of having a dedicated container for screen readers — is ‘focus management’. First, there is the visible content, which is generated using absolute positioned <div>’s and all sorts of other trickery. Then, there is the screen reader container, filled with “clean” content.

The “Visible Content” is hidden from assistive technology using aria-hidden, and doesn’t have any focusable targets. On the other hand, the Screen Reader Content is “visually hidden” but contains focusable targets.

This meant that every time a focusable target inside the screen reader container receives focus, we draw a faux focus ring to the corresponding object inside the visible content. This is required for sighted keyboard-only users, so that they know which link on the page has focus.

Text Resizing is More Than +/- Buttons

Most e-book readers have controls that allow users to increase the font size. But, what sets Scribd apart is that not only does it have the ability to adjust text size, it can also adapt to a user’s font size settings.

This allows users with low vision to enlarge the text on the screen beyond what’s normally possible with built in zoom control. The reader always adapts the layout based on the OS accessibility/font size setting, and any plug-ins or other assistive tech that the user may have installed for enlarging text.

This is done by detecting the base font size using JavaScript, and adjusting the page rendering system accordingly. Here’s an old but still valid article, if you’d like some more info: https://alistapart.com/article/fontresizing

Little Things

Dealing with Low Quality Text Alternatives

The quality of text alternatives provided by content creators may not always be high. Sometimes you’ll get unlabeled images and text alternatives that are no good, such as “Image”. We did our best to clean these using custom word filters and logic, so that images with low quality text alternatives don’t cause any confusion or negatively affect the reading experience.

Providing a Link to Audiobook Version

Another great thing about Scribd is that it gives you access to both unlimited books and audiobooks. This means that you can listen to the audiobook version of a book instead of using a screen reader. We provide a link to the audiobook version of the book, and vice versa.

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com?utm_source=medium&utm_medium=referral)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/11232/0*F7_Pfb1GkmsjW4gY)

Things We Should Improve

Screen Reader Only Content

If the content allows for it, always prefer on having a single version of your content. Using content that’s formatted for assistive technologies are great for an enriched user experience, but you’ll have to deal with other potential problems that will make the implementation trickier than you’d expect.

Things like text selection and focus indication will be a challenge to implement, and there may be other unexpected quirks. A great example of this was, during our usability tests, one of the users had an old version JAWS that didn’t support the aria-hidden attribute. This caused it to read some content twice due to the presence of text within the visible container.

A Simpler Search

Inline book search is located inside a dropdown, has a progress bar, and loads search results inside the dropdown asynchronously as the search is happening. Although all of the required accessibility features were in place, the interaction required to make a search was relatively complex. This became very apparent in our usability test results. All of our users were able to complete the task, but they rated it as time consuming.

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com?utm_source=medium&utm_medium=referral)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/9028/0*DHaJa5xsalBnkAMU)

I hope that provides some insight into how we created an accessible e-book reader for the Web. Please feel free to let me know if you have suggestions or if you have any concerns.

TL;DR Checklist

-

Text and controls have adequate color contrast when different themes are applied

-

Selected and highlighted text have adequate contrast

-

Text and controls are visible and operable in Windows High Contrast Mode

-

There’s an option to view a complete section with vertical scroll

-

There’s an option to view text aligned to one side

-

There’s an option to enlarge text

-

There’s an option to switch between at least one serif and sans-serif font

-

The bookmarking and note-taking options are always visible

-

Book title, current section and current page information is always visible, and can be located by assistive technology users easily

-

Headings are correctly generated from the content and logically nested

-

Focus remains visible when using a keyboard

-

Text flow and page number generation can adapt to changes in font size, including when a custom user style is applied

If you want to work on changing how the world reads, come join us! www.scribd.com/careers